Report on a survey of health and social problems created by the maladjustment of the native population in North Queensland, Northern Territory and northern Western Australia*.

*The survey occurred in June-July 1950 and Cook prepared this report in mid-1951

INTRODUCTORY:

Although the functions and responsibilities of Health and Native Administration in Australia, except in Commonwealth Territories, are prima facie exclusively the concern of the sovereign States, and although in the Northern Territory Native Affairs are directed by officers of the N.T. Administration Branch of the Department of Territories, the Commonwealth Department of Health, in the discharge of its prescribed duties, is directly concerned in several aspects of the activities of these separate authorities.

This Department is charged not only with the exclusion of quarantinable disease from Australia but also with the initiation and control of “campaigns for the prevention of disease in which more than one State is interested” and with the development of control methods.

Three factors which have in the past materially assisted the Commonwealth Quarantine Service in excluding quarantinable disease are in large measure now no longer operative:-

- The highly efficient health and medical services formerly maintained by European administrations to control and notify disease in adjacent parts of Asia have been impaired by recent political changes.

- The long time interval between infected overseas ports and Australian ports of debarkation, associated with maritime transport by sail or steam has been eliminated by the development of aviation.

- The narrow selection of airborne passengers amongst the well-to-do and less unhygienic classes no longer obtains – air transport now extends to categories of immigrant definitely at risk.

The security of Australia from imported communicable disease, quarantinable and other, must now depend largely upon maintaining local health and medical services at such a standard that the unsuspected introduction of insect borne contagious or bowel infection to any locality will not endanger it – normal conditions must be such that the risk of dissemination will be negligible.

Over a great part of the continent these conditions are probably adequately satisfied under State Health administration but there remains a considerable area, pre-dominantly within the tropics, which is sparsely settled by a white population of low natural increase, a substantial and rapidly increasing mixed blood and a larger but diminishing native population. Environmental conditions in this region are such as to contribute to the endemicity and epidemicity of dangerous communicable diseases likely to prevent successful white settlement or to involve considerable expense in control. The local community cannot unassisted maintain the standard of health and medical service necessary to ensure its own security. Meantime, the development of internal air lines and surface transport offers ample opportunity for rapid and unforeseen dissemination to more closely settled areas in adjacent States.

The region includes the Northern Territory, the Peninsula and Gulf Divisions of Queensland and the Kimberley Division of Western Australia.

Before white intrusion during the latter half of the nineteenth century this region was exclusively inhabited by aboriginals. Their number is unknown and estimates are wholly conjectural. Considering their mode of life and known distribution since white settlement it probably did not exceed 150,000.

Their only known contact with the outside world was that afforded by the transient seasonal visits of Macassars from the Celebes who came down in proas trepanging during the dry season to the northern coast of Arnhem land and the Gulf, establishing camps at certain favoured sites, to set up their curing deports. This trade, which had endured for centuries ceased in 1904.

The native Australian practised no agriculture nor animal husbandry; he domesticated no animal except the dog, established no village, built no dwelling, wore no clothing and acquired no property. Small family groups carrying practically no impediments except their primitive weapons moved as hunters over relatively extensive but definitely delimited, and for the most part tribally exclusive areas, living wholly upon the natural fauna and flora of the virgin bush. Stay in any camp was transient and its duration determined by the seasonal prevalence of game and vegetable food, the adequacy of water or the ceremonial requirements of tribal custom. Contact between families of the same tribe was of course frequent and on occasion sustained, contact between remote tribes did not normally occur, even to the extent of successive occupancy of the same camp site.

No permanent dwellings were erected at these camps. The native slept on the ground in the shelter of the trees or in the dry bed of a water course. For any length of stay in the dry season he erected a simple windbreak of brush, grass or bark to leeward of which he lay with his family and his dogs round a small fire. In the wet season a shelter of similar materials afforded protection from the rain. The basic principles of sanitation were unknown and no conscious hygienic precaution in the disposal of wastes and excreta was practised. The native lore comprehended no conception of communicable disease whether food-, water-, air-, or insect-borne, or transmissible by contact. Indeed, it may reasonable be surmised that his lonely, migrant existence in an environment characterised by bright sunlight, extremes of temperature and a seasonal succession of flood, fire and drought, supplemented by an effectual if undesigned intertribal quarantine, would eventually have permanently eliminated most of those infections which for generations have plagued the more static peoples of the human race settled in fixed communities in association with herds of domesticated animals and amidst the accumulated by by-products of human and animal existence.

It was inevitable that white settlement, whether violently or pacifically introduced, should effect fundamental changes in the native economy. On the Queensland Coast the white settlers, imbued with the traditional southern fear and distrust of the native and concerned to assure exclusive occupancy of the land for agricultural pursuits, endeavoured to drive the tribes away from the area of settlement, decimating them by organise battles and police “punitive” expeditions. To the west penetration was happily more pacific but even here powerful but then unrecognised influences contributed to the final outcome.

The effect of these influences was to render the normal native life more arduous and less attractive. Game was dispersed and many of the sources of vegetable food destroyed or denied. The best hunters and foragers were diverted to new types of labour, their dependants meantime becoming more and more reliant upon white bounty. Simultaneously, the younger native, employed in pursuits about the white settlement or mission was denied the opportunity to develop his hunting arts and skills whilst all were taught new wants which the old life could not satisfy. More and more dependent upon white employment or charity, the natives became concentrated upon limited areas where their natural foods were rapidly depleted by over-population and, where the traditional mode of life having been abandoned, they commenced a type of existence entirely alien to their experience and one which involved dangers which none – whether white or black – was concerned to observe or avert.

Concentration in camps, on missions or in the vicinity of white settlements, led to the creation of deplorable conditions of insanitation. The native, knowing nothing of the fundamentals of hygiene and enjoying no guidance from enlightened whites, brought to the new community life those negligent habits of excreta and waste disposal evolved under his previous security as a nomad. Ill-ventilated and unlighted huts built from waste material replaced the temporary brush whurlies. Camps were disposed without regard to water pollution – indeed to take advantage of the sandy ground, and to secure shelter from the cold southerly winds they were often sited in the river beds. The vicinity quickly became fouled with excreta and wastes, continuing so until the huts were burned and their occupants moved to another site by exasperated whites. This insanitation was a feature alike of mission and station camps. Indeed, fifty years after the foundation of some missions it can still be reported by official observers that no organised methods of night soil disposal have been devised for native use and only primitive arrangement exists for the Europeans.

In the final result, preventable disease introduced into this environment by immigration has effected, in the areas of pacific penetration, as tragic a decline in native population as did condoned slaughter in the region of hostile incursion.

POPULATION: The full blood population is not enumerated by Census but is estimated to be:

Exclusive of full blood aborigines, the population of the region approximates 54,000 (see Table I, page 27). Notable features are:-

- The heavy preponderance of males in the European population of the more sparsely settled areas;

- The comparatively large mixed blood coloured population in these localities (Table II, page 28)

Impressed by the administrative difficulties created by the sparsity of white settlement and confronted with the increased risks of the importation of dangerous infections to a region where the primitive mode of life of a great part of the population introduces special problems of disease control, the Commonwealth in 1950, undertook a preliminary survey of the area. The purpose was to collect data for Commonwealth and State discussions upon:

- The current standard of public health organisation and practice in tropical Australia;

- the requirements for adequate health administration in the region;

- the significance of the native and mixed blood population in public health administration;

- the means of implementing under Commonwealth-State co-operation the public health measures deemed to be necessary in respect of the coloured population.

This survey was made during June and July, 1950 the itinerary including-

Queensland: Cairns, Mona Mona, Port Douglas, Mossman, Gorge Mission, Daintree, Cooktown, Hope Vale, Thursday Island, Mapoon, Weipa, Aurukun, Mitchell R., Normanton, Morning Is., Burketown

Northern Territory: Borroloola, Roper Mission, Groote Is., Elcho Is., Yirrkala, Millingimbi, Darwin, Bagot, Berrima, Delissaville, Oenpelli, Goulburn Is., Crocker Is., Garden Point, Snake Bay, Bathurst Is., Port Keats, Pine Creek, Katherine, Maranboy, Beswick, Tandangal, Catfish, Tennant Ck, Phillip River, Alice Springs, Jay Creek, Yuendumu, Haast Bluff, Hermannsburg, Arltunga.

Western Australia. Wyndham, Karungie, Forrest River, Drysdale River, Derby.

South Australia. Ernabella.

INFORMATION:

Information collected during the survey inevitably included much having a bearing upon native administration.

Except in the Northern Territory, no strict colour discrimination is made between the full blood and the mixed blood natives and it is usual to find both living together in the native camps adjacent to townships or on missions.

Natives in Townships:

In the vicinity of townships natives casually employed and their dependants are everywhere subject to some degree of segregation. Their camps are sited on reserves or upon vacant land on the outskirts of town beyond the area served by the Civic water, light, sanitary and transport facilities. In most such areas they live in abject squalor, their quarters ranging from the traditional brush whurlies to more permanent structures improvised from scrap material salvaged from rubbish dumps or demolished buildings. These huts are dark, unventilated, overcrowded, without flooring, impossible to cleanse and lack culinary, ablution and sanitary facilities. The site is liberally strewn with organic and other refuse and faecal pollution of the soil is the rule.

In Darwin and Alice Springs, full blood native employed about towns are concentrated on special reserves but their conditions of existence are little better.

For water, natives are generally dependent upon some impermanent nearby soak or pool presenting evidence of gross animal or human pollution, or they may be under the necessity of carrying supplies in small amounts from some distant water point. As the dry season advances and surface sources fail, water must in certain localities be purchased from special carriers at considerable cost. In Normanton, Burketown and Derby this service attracts charges of from 5/- to 10/- for a 44 gallon drum at the height of the dry season. The strict limitation of water supply imposed by scarcity or cost precludes its use for ablution or domestic cleansing purposes.

In some camps notwithstanding these formidable obstacles, evidence of an effort to improve the standard of living is not lacking. Furniture may be improvised from packing cases, sleeping bunks or even old beds may be introduced but usually these are so dirty and dilapidated that they serve only to emphasise the general impression of filth and squalor. There was found no sustained or organised system of education for native children living these camps. This omission has recently been rectified, it is understood in the Northern Territory. Elsewhere, Church schools or unattached missioners may provide special opportunities for them but in the absence of these, whether temporary or permanent, the generality is afforded no instruction. The brighter and more eager may attend the public schools only in Queensland as long as their appearance offers no affront to the parents of other children.

In Queensland, the amount and quality of medical supervision varies in different localities. Nowhere is sanitary surveillance effective. Visits of inspection to the camps are made by Government and local authority health inspectors at long intervals, but no effective ensuing action is manifest. The camps are under the general surveillance of the local protector, usually the Officer-in-Charge of Police, and one senses a tendency to refrain from interference except when action may be necessary for disciplinary reasons. A conspicuous exception was the Gorge Mission at Mossman where the active interest of the Sergeant of Police has been expressed in a laudable effort to improve camp sanitation by the intelligent use of very limited resources.

Medical inspection of natives is not conducted as a routine, advice being sought only in case of illness or suspected disease. A general survey of natives for tuberculosis has, however, recently been completed throughout North Queensland by the State Department of Health and the occasion has been taken to make the first complete medical inspection attempted for some years. Hookworm surveys formerly maintained as a routine have latterly been largely abandoned, the Department now relying rather upon periodic mass treatment. For natives living under these conditions mass treatment is difficult to apply and suffers the disadvantage that one treatment engenders a false send of security in the impression that the patient is permanently cured. Initiation of investigation of the individual and the mass is now contingent upon the inspiration and zeal of interested third parties, all unfortunately too low. Such a survey, at the time of this enquiry, was being undertaken in Cooktown at the instance of the Matron of the Cooktown Hospital.

In the Northern Territory, organised and systematic medical supervision of the individual native ceased in 1939 with the divorce of native administration from the Medical Service. Intervention of the war and post-war staff embarrassments interrupted general medical surveys, which have now been resumed after an interval of a decade. It is worthy of mention here as indicative of the value of the close and continuing contact between the native and the Medical Service at times when health is not in question, that the native has naturally a child-like mistrust and fear of the white medical practitioner and his hospitals. Under the previous system in the Northern Territory for a period of twelve years, officers of the Medical Service moved freely as Protectors amongst the natives, acting as their agents in all their relations with the outside world. In the result they became identified by the native with the source of all those advantages, privileges and philanthropies accorded him by the protection system. In this way the fear of medical inspection was eventually overcome in most areas of contact and doubtless would shortly have been eliminated throughout the Territory. Today a new generation which has not known or which has forgotten this influence predominates in the native community and it is difficult even on missions and Government stations for a visiting medical officer to gain access to more than about two-thirds of the population. As natives in the vicinity of towns live on reserves under departmental control, sanitary inspections conducted by officers of the Northern Territory Medical Service can achieve results only on the compliance of the Native Affairs Department with the recommendations of the inspecting officer. There was little evidence at the time of this enquiry that compliance was freely forthcoming and it appeared that inspections were few and conducted only at long intervals.

In Western Australia for some years annual medical surveys of all natives in contact have been conducted by special medical officers but the value of the work has been somewhat impaired by the primitive nature of native hospital accommodation. Sanitary inspection has been repeated annually since 1947 but has achieved little improvement owing to the inability of the individual and of the Departments concerned to provide labour, material and funds for the work ordered.

Natives on Settlements and Missions:

It may be accepted that the purpose of a settlement in a tribal area is primarily by appropriate education to adapt the native to his inevitable ultimate contact with white civilization so that he may enjoy such advantages as it may offer without suffering with degradation which overwhelms the unprepared. Associated with this activity will be medical care of the sick and sustenance of the aged and infirm. For Government stations a further purpose, indeed sometimes the principal purpose, may be to attract and hold native away from settled areas and to serve as disciplinary centres.

If complete adaption is to be attained, education must far transcend the early concept of preaching the Gospel and teaching rudimentary English, writing and arithmetic. The end result of this type of training has been a youth unqualified for comfortable existence either in a native or a white society, a prey to a multitude of newly acquired wants and impulses which his untutored ability cannot gratify in the environment into which he is discharged. The choice confronting him is one between permanent dependence upon a mission or social ostracism and economic insecurity on the outskirts of white settlement.

Native education must comprehend complete reformation of the individual’s character by developing in him those qualities with which his inheritance and experience have not endowed him but which are essential to his successful integration into white society. These include i) an appreciation of property and its relation to personal and social progress. It must ii) procure his full consciousness of and habitual compliance with the principles of personal and communal hygiene and iii) it must enable him unaided to produce for himself the means for gratifying the new wants which settlement contacts have stirred within him.

The success of a settlement can only be measured by its achievements in the pursuit of all three of these objectives and unless they form the basis of its policy and the main purpose of its labours, the enterprise were better terminated. Judged by these standards, no settlement visited could evoke congratulatory comment, on the contrary the predominant emotion inspired by most was one of despair.

(a) Policy

Left to themselves in their tribal areas natives are largely secure from communicable disease introduced by white agency. Concentrated in settlements they suffer an abnormal exposure to these infections under conditions designed to favour dissemination. Unless the policy of the settlement can justify this incursion and includes compensating activities, the Health Authority may well question its wisdom.

Settlements create in the native new wants which they cease to gratify upon his leaving school, so that in adult life he is impelled into the towns, to reach which he may traverse long distances, destroying the natural inter-tribal quarantine which normally would exist. At some Government settlements the attempt is made, at considerable expense, to aver this migration by feeding natives at the settlement. Apart from the fact that this may be challenged as a pauperising extravagance the diet is often ill-balanced and inadequate.

Few superintendents interviewed were able even broadly to define the policies of the organizations they represented. Indeed it seemed that many have no positive or sustained purpose beyond propagation of the Gospel. On individual settlements there has been no continuity of policy or purpose over the years. It has been unusual of any native station for successive superintendents over any length of time to sustain in the face of heartbreaking frustration, more than a tepid interest in any one of the settlement’s various activities. The zeal devoted by one incumbent at any one time to education, hygiene instruction, medical care, agriculture, pastoral pursuits or other activity has fluctuated in intensity throughout his period of office, whilst over a period marked by a succession of changes in superintendent, all enterprises have passed through period of busy interest, alternating with complete neglect, according to the whim and the capacity of the individual at the time in charge.

(b) Site:

Several settlements are for one or many reasons unsuitably sited and it may well be necessary to consider abandoning these. Their experience emphasises the importance of subjecting proposals to establish settlements to a strict scrutiny to ensure that the site complies with certain fundamental requirements.

- The desirability of commencing or accelerating de-tribalisation in the area must be beyond doubt.

- The locality must be suitable for pastoral, agricultural, horticultural or other industrial pursuit, promising an appropriate diet for the native under the newly imposed mode of life and adequate opportunity for his economic education.

- The disease risks – imported or indigenous – must have been carefully assessed, and their control assured.

- Potable water must be permanently available in adequate supply for sustained occupation.

- The food potential must be sufficient in quantity and adequate in quality for sustained occupation by the estimated population and for temporary accession.

- The site must be readily accessible for medical and administrative supervision for the delivery of supplementary supplies.

Too often selection of the site has been made on the experience of one or two travellers who have reported the water supply as inexhaustible, the soil arable, and the locality free from disease. Under the heavy load imposed by a static population totalling some hundreds, the water supply fails and the soil, inadequately watered and heavily cropped, proved unable to sustain its initial fertility.

Shortage of water means dispersion of stock, failure of horticulture, poverty of diet, absence of ablution and laundry facilities, and a perpetually low standard of insanitary existence; there being evident reluctance to admit the error and abandon the enterprise.

(c) Access:

Sometimes there is no means of access to a settlement except by air and the station may be some miles from the aerodrome, and unprovided with reliable surface transport. Most settlements recently visited were cut off from surface communication with the outside world for many months. Some relied exclusively on road transport – roads had been destroyed by flood or the vehicle was out of commission. Some rely exclusively on boats – the boat was wrecked or unseaworthy. Some were inaccessible even by air owing to the nature of the terrain in which the settlement was situated or to neglect of the airstrip.

(d) Staff:

The medical supervision of staff on appointment and subsequently is not adequate. Hookworm, tuberculosis, leprosy and malaria have been introduced to new tribal areas by mission staffs, European and native. Four European missionaries have contacted leprosy on missions in the Northern Territory and Western Australia in the last quarter century.

(e) Diet:

Strict supervision of diet is long overdue upon settlements. There is a strong trend towards using a vegetarian diet, bulk masking its deficiencies and ill-balance. The method of feeding varies widely from service of a cooked meal three time a day to the issue of dry rations once weekly. It is impossible accurately to assess the caloric value or balance of any ration from such information as can be supplied on the settlement. At some, a hypothetical native diet is supplemented by an issue of heavy meal-bread or a pannikin of flour which, cooked as damper, will assuage hunger and probably not be supplemented. Outbreaks of scurvy have resulted.

The tribal native diet is high in animal protein, animal fats, minerals and vitamins. Even the best partial European diets, substituted in settlements, are deficient in these items and are furthermore calorically inadequate for older children and young adults.

Failure of soil or water and exhaustion of vegetable crops seriously impair the settlement economy. At such times natives may be given a limited canned ration or “sent bush”.

Generous social service payments have made no visible difference to the diet scale on some settlements. On others liberal issues of marmite, aktavite, cocoa, canned fruit and dried milk are made to certain sections of the population. Apart from the fact that this is an extravagant method of feeding in a community which should endeavour to be self-supporting, native children are in this way taught to rely upon a form of diet which will not be available to them in adult years, since they are taught neither the means of producing equivalents nor a vocation which will provide the means of purchase. Paradoxically the social service payment may prove an evil influence by encouraging settlements to take the easy course of purchasing canned food instead of maintaining herds and plantations from which the native may learn animal husbandry and horticulture to produce a wide range of foodstuffs for himself now and in the future.

(f) Sanitation:

The standard of sanitation and hygiene education on settlements is important not only because of the concentration of natives there, which of itself constitutes a disease risk under unsatisfactory conditions, but also because the native himself, having no community background and no knowledge of the risks and obligations of community life, must learn these at the settlement. Generally speaking, native settlements, whether Government or mission, may be described as places where for no demonstrable reason, a large number of susceptible natives, fed a deficient diet, are concentrated under insanitary conditions in contact with communicable disease introduced from elsewhere. It is important that the Health Authority be empowered to exercise stricter control upon such stations.

- Water Supply: Water is commonly drawn from surface sources used also for ablution and exposed to faecal contamination and the drainage of the camp. Where drawn from shallow wells these are usually open, unprotected and exposed to human and animal contamination. Distribution is usually by bucket or drum inevitably contaminated in transit. Where distribution is effected by a limited reticulation, leaking joints and defective taps cause ground pooling, and potential anopheline breeding.

- Nightsoil Disposal: Usually a primitive bucket or pit service is provided for the staff and immediate vicinity of the administrative buildings and an inadequate service or none whatever for the natives. Collection is usually in improvised buckets under pansteads which are not fly-proof. The soil in the vicinity of privies is commonly polluted. Disposal of pan contents too often is by trenching in the garden. In no case observed was the method of trenching satisfactory.

Trenching is uncontrolled and left to the natives detailed for the task – sometimes girls from the dormitory. The siting of trenches is haphazard and barefoot sanitary details are permitted to traverse and retraverse polluted areas on successive days, even on stations where hookworm is endemic.

On certain Government stations in the Northern Territory, more particularly in heavy rainfall area, incinerator latrines have been installed. The burning out of these has been neither supervised nor regular; the pedestals were found over-loaded and often in gross disrepair.

It is commonly insisted by superintendents of settlements and others that natives cannot be trained to use latrines. Ample evidence is available even on their own stations to refute this statement. Even where latrines had been permitted to fall into a condition of extreme discomfort, gross insanitation and dangerous disrepair, it was noticeable that considerations neither of comfort nor safety prevented continuance of their use by those natives who had learnt to avoid promiscuous pollution of the soil.

- Ablution: Only occasionally has sufficient provision been made for bathing and personal ablution. Where these are provided they are usually in disrepair or without sufficient water. The necessity of training natives in personal cleanliness at the toilet and before handling food seems to have generally overlooked and only exceptionally are the necessary facilities readily available. These generalizations apply as well to Government stations as to missions.

- Service of Food: On most settlements improvement in the mode of service of food is required. If the food is such that it cannot be eaten from the hand, it is commonly served into an unclean pannikin or jam tin presented by the recipient and consumed in the vicinity of the kitchen on the ground. Rarely is an effort made to teach clean feeding habits or to provide the necessary washing facilities. Lamentably, in the isolated cases where a high standard in this and other respects is achieved with school children, no opportunity for future practice of these acquired virtues is assured for them. On leaving school they are returned to the filth and low standards at the native camp, which by training and background they have learned to eschew.

- On no station devoted to the care of full bloods was a properly organized system of wastes disposal observed. Accumulations of discarded organic matter provide breeding ground for flies whilst sullage and waste water are permitted to foul streams or to flood the ground in the settlement itself. The dangerous anopheline A.punctualatus ferauti was discovered breeding in pools of this type at the Government station at Berrima, near Darwin, at a time when a native case of malaria had been removed from the station.

- Housing: Induction of the native into community life has not included a sustained effort to inculcate the value of light and ventilation in dwellings. Exception may be made here of certain Queensland missions. For the rest, there is a tendency to herd the natives into dark ill-ventilated, overcrowded shanties, improvised from waste materials and with no provision for cleansing the floor.

The cost of building conventional types of home is prohibitive. There is therefore an urgent need for the development of types of construction permitting the erection of hygienic dwellings of pleasing appearance using local materials and organized self-help labour groups.

- Medical Aid: The appointment of one or more trained nurses to the settlement staff either as a special posting or as the wives of other officers is usual on the missions of certain religious denominations but not of all, nor was it found to be the rule of Government stations in the Northern Territory. Such appointments are necessary –

- to maintain constant supervision of health;

- to provide trained observation and enlightened interpretation of symptoms for the information of medical officers in touch by radio communication and to prevent wasteful exploitation of the Flying Doctor Service;

- to give appropriate treatment for minor maladies, the successful treatment of which will encourage native confidence in modern medical practice;

- to supervise the standards of hygiene, to direct measures of control of communicable disease, to educate native mothers in child health and to provide superintendents with intelligent advice on medical and sanitary problems. Particularly is this so where sufferers from leprosy are detained under observation on missions pending the provision of special accommodation for their reception and treatment elsewhere.

Where there is no trained nurse on the settlement staff it was found –

- medical aid posts were poorly stocked, inconvenient ill-equipped and unhygienic. Commonly, as on Delissaville, a dusty corner of the general stored was used for consultation, the limited supply of drugs and dressings being stocked on shelves with other goods;

- unenlightened and liberal use of dangerous drugs including the sulphonamides, involves risk to native and white patients alike. It may here be remarked that it may at any time become necessary to issue some of the more modern anti-malarial drugs for use on native settlements. Settlements without properly trained staff could not with confidence by supplied with these preparations.

In Queensland medical inspection is neither regular nor systematic. Where a medical practitioner is within a convenient distance, visits may be arranged at monthly or quarterly intervals. On the more remote missions, like those on the Gulf, visits by a medical practitioner are infrequent. The occasion of a visit by a medical officer is not taken to arrange a general inspection of the natives – usually only those presented by the mission for advice are examined. Communication is unsatisfactory, all the remote stations visited being equipped with wireless transmission sets and working a schedule with Native Affairs base station at Thursday Island or Flying Doctor Station at Cloncurry.

In the Northern Territory the aerial medical service maintained by the Commonwealth permits both regular routine flights and special visits to native stations. All stations are equipped with wireless and work schedules with Cloncurry or Darwin. However, it was not found customary to send a medical officer on routine, or necessarily even on special flights. The pilot was accompanied by a trained nurse and the aircraft was used rather as an ambulance. This effects a considerable economy in medical officers’ time but involves neglect of opportunity to submit mission and other people to frequent inspection.

In Western Australia missions are equipped with radio transmission and receiving sets w/t and communicate with bases on Wyndham and Derby (except Drysdale River which works Darwin). A charter plane is available at Derby to serve as an aerial ambulance and to transport nurse and doctor. A travelling medical officer may use air or road transport to cover all settled areas between Derby and Wyndham and is intended to be based at Derby, but he is temporarily posted to Wyndham. A trained nurse holding Infant Welfare Certifications tours the country between Broome and Wyndham and visits native families in their homes. Complete medical inspection of native and mission is routine practice in Western Australia.

On a number of settlements in Queensland and the Northern Territory one sensed an incapacity or reluctance to muster natives for medical inspection as if the superintendent felt insecure of his authority and was unwilling to risk humiliation by issuing an order which might be successfully defied or making a request with which some might reuse to comply.

(g) Education:

There is a wide diversity both in the target standard of general education and in the energy with which instruction is imparted. Some missions appoint qualified teachers to their staffs but a great many leave instruction to untrained persons. At some Queensland missions zealous perseverance has brought the pupils to the standard of the State Qualifying Certificate. Elsewhere standards are much lower and at still others in the Northern Territory, schooling had for one reason or another been discontinued.

At some missions it is boasted as an advanced policy of high merit that natives are taught in their own language. Whilst giving full credit to the responsible missionaries for their zeal and application in learning the native tongue, and whilst admitting the advantages of this mode of instruction in the early schooling period, there are a number of self evident objections to this practice which should exclude it from Government policy:-

- The objective of education, if there be any, is to fit the native for social intercourse with the European and to enable him to take his place in the white community. In areas, if such there be where there is no purpose in such an objective, there would appear to be no reason to disrupt the native’s normal tribal education. If this objective be admitted, the pupil must be taught English, the common tongue which will permit him wide intercourse not only with persons of European stock but with other natives whose dialect is unfamiliar to him.

- Restriction of the scholar to the native tongue must limit him within the confines of the native culture. If he is to have the advantage of the wider European culture, his thought and expression must be served with the vehicle of that wider culture and not be suppressed by the inadequacies of his own tongue or that modicum of it which a European teacher can comprehend.

- Even on the stations where schooling in the native language is undertaken, the number of the mission staff fully understanding the native speech is limited. Transfer of a teacher may result in impairment of even discontinuance of the studies.

- The system is only applicable where all the natives on the station speak the same language and can therefore only be applied in a few localities. Free interchange of teachers is restricted and one section of the native population is educated to a different standard to those elsewhere.

Hygiene education is everywhere neglected. Indeed at no settlement visited was staff less in need of instruction in camp sanitation than were the natives themselves. The principles of sanitation must be inculcated by example as well as by precept. Any effort to train natives in hygiene must be aborted whilst they continue to see around them evidence of official indifference to its first principles and whilst they are denied opportunities and facilities for putting their teaching into practice.

(h) Industry:

On the whole the value, the necessity of productive industry in the education of the native and the economy of the settlement, seem to be but dimly appreciated. On certain Queensland missions fortunately situated, it is true that efforts attended by some success have been made to develop logging, horticulture and the like as lucrative enterprises, and at Ernabella in South Australia sheep farming shows promise.

Even here, however, emphasis seems to be upon employing the native profitably as a servant of the mission, giving him a store credit or a wage for his service. Where agriculture or horticulture are undertaken on a liberal scale, the objective is to feed the native with produce of the station rather than to teach him as an individual to be self-reliant and self-supporting. It has already been remarked that the excessive use of garden produce has created important diet deficiencies which have serious impaired native health. No where apparently has the alternative possibility of using garden produce as a means of trade to purchase supplementary foods been seriously considered.

Where horticulture is the only industry and where, as it not unusual, the crop fails for lack of water, depletion of the soil, salt water flooding or other cause, the native has an object lesson in the futility of European enterprise, the psychological effect of which is incalculable. Nowhere has the native been successfully trained in any avocation promising him independence of the mission and secure self-support in a productive industry. Indeed the object lesson of the recurrent failure of crops and the spasmodic exploitation of industries on some mission, must together have created in the native an attitude of mind discrediting white endeavour.

At Elcho Island and Snake Bay in the Northern Territory timber milling is undertaken as a major settlement enterprise, the natives being paid a store credit or wage for labour. The stands of timber are limited and are being rapidly exhausted. No re-afforestation is undertaken. Apart from the economic waste of this practice, the native is paid for service, the educational emphasis of which is destruction for immediate profit without a care for future opportunities of earning.

Along the northern coast of Arnhem Land, trepang abounds and suitably treated could no doubt command a profitable and permanent market in South-East Asia. These waters, for centuries until 1904, provided wealth for Malays who visited them each year from Macassar and elsewhere. Several missions are established along this coast, some of them on the very bays and islands favoured by the Malays for the erection of their curing deports. None appears to have given any thought to re-establishing the industry as a permanent avocation likely to give the native a stable foothold in the Australian economy.

In pastoral country, cattle raising has not been carried beyond the bare necessity of supplying beef for the settlement or for an occasional sale to provide ready money for the mission. Most missions are short of fresh milk and meat but few attempt to run adequate herds of goats or cattle. Even where these herds are maintained, husbandry is poor and commensurate advantage does not always accrue. One station for instance imported large quantities of milk, and had a herd of goats which did not include one buck.

(i) Sport:

Strangely enough, although the native is an apt pupil in any form of athletic sport or skill, no mission or Government settlement visited had undertaken the organisation of team sports or taught even the rudiments of a football code. Footballs had been issued here and there, but they served only for purposeless kicking and no sports fields were seen. The value of organised team sports not only in giving attraction to mission life but in developing social community with Australian youth may well be inestimable.

Endemic Disease:

The advance of endemic disease is shown to be so closely related to the establishment of native settlements and the lack of medical guidance in Native Administration that it warrants study at same length. In particular, the history of Leprosy in this region illustrates the disease risks created by European settlement and gives warning of a menace unsuspected by the Australian public at large.

Leprosy is by far the most important of the endemic diseases in Northern Australia, In the amount of disability it occasions and in the cast of its treatment and control, it far transcends any other condition engaging medical attention in this region.

Introduced late in the nineteenth century by infected coloured aliens, Leprosy at first spread sporadically amongst the isolated remnants of the almost extinct native tribes in contact with European settlement in the areas affected. Evidence of increased activity amongst natives and the involvement of white settlers in contact with them led in 1924-25 to a special investigation to ascertain its actual incidence and to determine appropriate measures for its control and eradication. The survey was conducted by the Commonwealth Department of Health in conjunction with the London School of Tropical Medicine and disclosed:-

(a) Incidence was not high. In Queensland it occurred sporadically in several localities to which it had been introduced by Melanesian agriculture labourers and Chinese miners but it was prevented from attaining formidable properties by-

- the sparsity of native population resulting from the violent agencies of depopulation which had marked the close of the nineteenth century and from the State’s policy of concentrating the majority of natives from developed areas on supervised settlements;

- the application of the Leprosy Act 1892 under which patients should be actively sought and isolated;

- the comparative infrequency of intimate association between European and native.

In Western Australia and the Northern Territory cases were few (19 and 26 respectively). Infection had been largely confined to natives in areas of extreme depopulation near mining fields and townships but Mission activity in territory hitherto inviolate was progressively breaking down the natural inter-tribal quarantine which had formerly protected intact tribes from infective contact. In addition the prolonged residence of native lepers on Missions in close association with migrant natives from unaffected areas portended an early and wide dissemination to new localities.

(b) Control had checked progress in Queensland but was incomplete and did not promise early eradication. More intense and frequent search for new cases and more careful and sustained review of suspects and contacts were required.

No effectual measures of control had been applied in the Kimberley Division of Western Australia or in the Northern Territory. In neither of these areas was a suitable isolation hospital maintained, nor was there an adequate medical and health service. Prompt repair of these deficiencies was recommend, an intensive campaign for the early detection of cases and the prevention of dissemination being required immediately.

(c) For the Kimberly Division of Western Australia and for the Northern Territory, an organized full-time Medical Service was desirable. It was recommended that this Service should be endowed with all the powers and functions vested by legislation in the Chief Protector of Aboriginals in order that the prophylaxis of leprosy could be assisted by the control of native employment and migration, the strict supervision and direction of Missions and uninterrupted access to the native individual and mass, for purposes of medical examination.

Following the 1924-25 report no immediate action was taken in any of the areas surveyed. In Queensland, current measures of control were continued and in 1939, natives hitherto detained for isolation and treatment at Peel Island in Moreton Bay were transferred to a new hospital on Fantome Island in the Palms group. This institution had been especially erected for the reception of both full blood and mixed blood lepers from all parts of the State. From that date until December 31st, 1950, the number of patients accommodated on Fantome Island has consistently approximated to 70, admissions being offset by deaths and discharges. It may then be inferred that although no great progress towards eradication is yet apparent, at least the disease is under control, the incidents amongst natives being as 1:300.

In Western Australia no useful action was taken until 1935 when a Medical Officer was appointed to the Native Affairs Department to conduct medical inspections of natives throughout the State. Special accommodation for lepers was not provided until 1937. In the meantime, native cases had been concentrated in a camp near the Native Hospital at Derby, where no effective control was exercised to prevent escape or [social] intercourse with the uninfected. A number of uninfected natives erroneously suspected of leprosy by laymen were from time to time detained in this camp to await confirmation of the diagnosis by a Medical Officer and of these a number developed the disease after returning to their own country, where they became an unsuspected source of infection to their fellow tribesmen.

Others were detained on Mission Stations under conditions of imperfect isolation which led to the infection of still more natives and of missionaries.

In 1932, 1934 and 1935 three drafts of leper patients, totalling 69, were transferred by lugger from Derby to Channel Island, Darwin. The embarrassments of this means of transport – the contracting skipper subsequently himself became a leper – led to its abandonment and decided the Western Australian Government to build its own leprosarium at Derby. This institution was opened in 1937. By 1940 the number of patients accommodated had reached 197 and in 1950 – 302. These figures are, of course, exclusive of the survivors of the 68 transferred to Darwin. Related to the estimated native population of the region the figure for 1950 gives a present overall incidence of roughly 1:18.

In the Northern Territory, action in terms of the report was taken in 1927 when a Medical Officer with experience in Tropical Medicine was appointed Chief Medical Officer and Chief Protector of Aboriginals to reorganize the medical and health services of the Territory and, in particular, to devise and apply effectual measures for the control of Leprosy. Active search for cases was commenced and measures to reduce opportunities for dissemination were taken. No special accommodation for the isolation and treatment of cases was available, however, until 1932, when a new Leprosarium was opened on Channel Island. In the meantime, isolation was attempted in improvised quarters at Darwin Hospital, on Missions and elsewhere. The incubation period of Leprosy in natives is approximately 4 years and it was not to be expected that any effect of attempted control would be manifest until 1933 or later. In that year 56 Northern Territory natives were detained under treatment at Channel Island.

Subsequently, until 1939 the number of cases remained constant in the vicinity of 60. Native admissions averaged 16 annually and active search for new cases throughout the Territory revealed no increase in incidence. Indeed there appeared reasonable promise of successfully maintained control as in Queensland, or even of ultimate eradication.

In 1939, however, with the establishment of a Native Affairs Department of the Northern Territory Administration as a distinct entity, many of the control measures permitted by the previous form of establishment became impracticable and inoperative. Admissions fell significantly in the ensuing year but this probably reflected the discontinuance of organized surveillance as much as improvement in the epidemiological situation. Following the outbreak of war with Japan in 1942, the A.M.F. assumed full administrative control of the endemic areas and search appears to have ceased. The Commonwealth Department of Health resumed operation in the Northern Territory in 1946 but owing to staffing difficulties it was not possible to recommence mass surveys of natives until 1950. As at June 30th, 1951, the Deputy Director of Health, Darwin reports 201 full blood and 34 mixed blood lepers as in institutions or under surveillance on Missions and elsewhere pending the provision of additional leprosarium accommodation. Related to the estimated population of the area, these figures already represent an incidence of 1:25 for full blood and 1:60 for mixed blood natives, but they are incomplete and will be increased as surveys proceed.

The number of Europeans tracing infection with leprosy to exposure to natives and halfcastes in the Northern Territory is now not less than 20. If full information were available regarding cases isolated in State Institutions the number might well be found to be more. These infections date from a period when Leprosy was much less prevalent and the white population much less numerous than that of today. In the next few years the number of Europeans infected in the Territory and seeking treatment there or in Southern States may be considerable.

A disturbing aspect of the present epidemiology in natives is the heavy incidence upon children, an entirely new feature marking established endemicity.

Missions and Native Settlements play an important part in the dissemination of Leprosy by:-

(a) breaking down the natural barriers of intertribal quarantine; and

(b) carefree herding together of the susceptible and the infected. Two instances may be cited from the experience of Western Australia.

Beagle Bay Mission had been established (nearly thirty years before Leprosy first appeared there. In 1921 Leprosy was introduced in the Mission by a native from Derby. By 1932 fifteen native lepers had been removed from the Mission and by 1940 the total had reached 54.

In 1924 Leprosy was shown to be confined to the Fitzroy River Basin. In 1933 a case was discovered on Munja Government Station on Walcott Inlet, beyond the Ping Leopold Range. During the next four years 21 new cases were found here and up to 1940, twenty-five more, most of whom traced their infection to contact on Munja, were discovered in the Halls Creek-Wyndham area.

Appreciation of the inadequacies of Mission “isolation” as here revealed inevitably occasion misgivings for the immediate future in the Northern Territory, where, for a time at least, many leper children must be detained on Missions and Settlements until alternative accommodation is provided.

The history of Leprosy in Queensland, Western Australian and the Northern Territory demonstrates the necessity for energetic and sustained prophylaxis in the interest alike of native and European. The required prophylactic measures cannot be effectively applied without the closest liaison between the Medical Service and the Native Affairs Department, because they involve not only strict surveillance of the individual and repeated medical examination of the mass of native population but also the intelligent control of migration, the strict supervision of Missions and the regulation of native employment.

Hookworm: Hookworm was recognized as a feature of tropical Queensland epidemiology for many years before any energetic action was taken to assess its incident or to prevent its diffusion.

In 1919 Sawyer of the Rockefeller Foundation reported that on the East Coast hookworm had an incidence of 18% in the population, exclusive of aboriginals, and 81% in natives. He remarked in 1920 – “It is only occasionally that a community is found where more than 30% of white people are infected – aborigines under similar conditions are apt to be all infected.”

The factors particularly contributing to the high incidence in natives were their practice of promiscuous defaecation and their unshod habit.

The Hookworm campaign in Queensland during the period 1919-21 revealed the following rates amongst natives on mission stations:-

By contrast, the incidence in natives living at large outside Missions was 19% – a rate comparable to that of the general population. At all Missions, investigating officers reported that gross conditions of insanitation existed in respect of the disposal of night soil. No latrine provision was made for natives and promiscuous defaecation was the rule.

After 30 years the rate at Mona Mona and Daintree (Port Douglas) is still 70%. During the same interval incident at the Government Station at Palm Island has been reduced from 77.2% to 9% by improvement of sanitation and by mass treatment.

Of recent years the State Hookworm Campaign has abandoned native surveys in favour of mass treatment. Two disadvantages of this policy revealed by the enquiry were:-

(a) Superintendents of Missions and others are apt to believe that one treatment effects permanent cure and take no further action to improve sanitation or check reinfection;

(b) Not all are conscientious in the administration of treatment. At Mornington Island, drugs for mass treatment issued some considerable time ago were still unused – this notwithstanding that the clinical history of Bentinck Islanders on the Mission suggested a heavy Hookworm infestation rate.

A survey of the Northern Territory was made by Baldwin and Cooling for the Rockefeller Foundation in 1922. Rates reported included:

Promiscuous defaecation was here also the rule rather than exception on Missions and elsewhere. Even in the town of Darwin no latrine accommodation was available for natives in employment. Employers would not incur the expense of providing separate latrines for their employees and would not permit them to use the conveniences provided for the family. Natives were therefore under the necessity of fouling the damp ground in the bush adjacent to their places of employment.

The Mission at Elcho Island was in process of establishment at the time of the survey. Elcho Islanders themselves were free from Hookworm, infestation being confined to native labour imported by the Missionaries from an endemic area to assist in preliminary work. Subsequently, Hookworm became heavily endemic here.

A survey of the North of Western Australia was made by Baldwin in 1922 when the following rates were reported amongst natives:-

As in Queensland and the Northern Territory, promiscuous defaecation was the rule. No organized sanitary system was provided on Missions and no special accommodation for native employees was available in the towns.

Many areas throughout the North found free by the Hookworm Campaign have since become endemic foci and Mission agency in this development is clearly shown.

Notable amongst these are Roper River Mission in the Northern Territory and Derby and Sunday Island in Western Australia. At Mornington Island on the Gulf of Carpentaria, incidence on the Mission was 84%. On the mainland opposite, Hookworm was not found and according to Charlton who conducted the survey, the only natives free from infection on Mornington Island were those who had recently arrived there from the mainland. The incidence on Mitchell River Mission (Charlton) was 20% and amongst Peninsula natives nearby, 5%. Many of the parasitised in the latter group had from time to time visited the Mitchell River Mission.

To minimise dispersion in this way it was the practice in later years in the Northern Territory for the Chief Medical Officer, as Chief Protector, to forbid the movement of Mission Staff and natives from endemic to non-endemic areas until and unless they were shown to be parasite free.

Since the war, Hookworm has become an important factor in the debilitation of natives in many areas, particularly on Missions and Settlements. Haemoglobin readings as low as 40% are not uncommonly reported. Such are found chiefly where a diet deficient in iron and the Vitamin B . complex already makes it difficult for the individual to maintain a normal level.

Malaria: The Peninsula and Gulf Division of Queensland, that portion of the Northern Territory lying north of the 19th parallel of South Latitude and the Kimberley Division of Western Australia are potentially malarial areas. A number of anophelines known to be capable of serving as vectors are indigenous to the region and from time to time in the past the synchronism of special entomological and demographic conditions has produced serious epidemics of malignant malaria associated with heavy mortality in natives and Europeans.

Malaria in inter-epidemic intervals occurs sporadically but is confined to a minimal incidence by the sparsity of population and the normally short duration of vector prevalence in most localities.

Control of Malaria in this region must depend principally upon control of the case and of the carrier and for this to be effectual the Health Services must be afforded full freedom of action in respect of the examination, surveillance, treatment and detention of natives.

Tuberculosis: For many years, fears have been entertained that Tuberculosis will attain a high incidence in natives in the North and cause considerable morbidity and mortality. Much of the depopulation amongst aborigines in Southern Australia has been ascribed to Tuberculosis but in the North, except in a few well-defined areas, this infection has not attained serious proportions, in spite of its occasional introduction. Possible this anomaly is to be explained by:-

- the sparsity of white settlement in areas of greatest native population density minimising opportunities of exposure;

- the normal open air life of the native.

If this be so, it must be expected that if the white population increases and the concentration of natives on settlement proceeds, Tuberculosis will become a serious problem unless hygiene is improved and extensive immunization is undertaken. This expectation is in conformity with experience in analogous condition of Leprosy which, introduced from abroad to areas of relatively dense alien population, for several years spread only sporadically amongst the few scattered remnants of native tribes in immediate contact but later assumed epidemic proportions when introduced to the abnormal conditions of association and squalor associated with mission and settlement life.

That the native has in the past freely experienced and safely survived exposure to Tuberculosis is established by surveys recently undertaken.

In Western Australia, King et al found that in remote desert tribes that the percentage of reactors to tuberculin was as low as 20%, although amongst natives long resident on missions it was as high as 70%. The overall conversion rate in each age group did not show any striking dissimilarity from that to be expected from experience in the white population. The incidence of Pulmonary Tuberculosis in natives was less than 5 per 1000. This was not considered significant and represented an incidence of the disease lower than that in the general Australian community.

In Queensland, a survey conducted by the State Department of Health revealed that the conversion rate in natives is significantly higher than in white Australians in all age groups over five years. The discrepancy was most marked upon the eldest and more permanent settlements. The apparent inconsistency in Queensland and Western Australian figures is therefore probably attributable to the greater intensity and longer duration of settlement concentration in Queensland and is in conformity with the expectation already expressed that protracted residence under existing settlement conditions will raise the incidence of Tuberculosis.

In the Northern Territory, mass Mantoux testing and B.C.G. inoculation are preceding but comparable figures to those supplied for Western Australia and Queensland are not yet available. From data so far collected it is, however, concluded that Tuberculosis is not as serious a public health problem as are Leprosy and Hookworm.

Mixed Blood Natives:

In the Northern Territory and in Western Australia the mixed blood component of the population presents a complex problem quite separate from that of the native generally.

In both States and in the Territory legal provisions exist for excluding the mixed blood from the operation of the law relating to the aboriginal but policy in the exercise of these has not been similar. In Queensland no official discrimination is made between the full blood and mixed blood natives unless the individual has on his own initiative, attained a standard permitting exemption. Three agencies have prevented in Queensland the development of those special anomalies which have created a distinct mixed blood problem in the Northern Territory and Western Australia:-

- The overwhelming preponderance of Europeans in the greater part of the State;

- The identification of the mixed blood with the full blood native;

- The long standing policy of concentrating on settlements native remnants from the more developed areas

In the Northern Territory, the more potent agencies of native depopulation which characterized the pioneering period in Queensland have never operated and there have always been extensive areas beyond the limit of European settlement carrying large numbers of full blood natives little influenced by white intrusion. Whilst full blood depopulation has proceeded in the area of European domination, a mixed blood community with a high rate of natural increase has grown to replace it. This new component, reared in contact with but socially apart from the white community, had nevertheless no common interest, biological, economic or social, with its full blood ancestors. Whereas as in Queensland the European population has progressed rapidly, in the Territory its natural increase has been abnormally low. The mixed blood population largely segregated from the black and living amongst but not with the white, soon attained such numerical strength that its secure integration into the local society has become a matter of urgency.

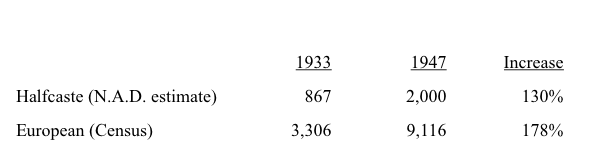

The white population of the Northern Territory at Census 1933 and 1947 is shown in the subjoined table compared to the estimated contemporary halfcaste population. Many halfcastes, it must be remembered, are born to full blood mothers in native camps and whilst living there would not be enumerated by the Census. The official Native Affairs estimate for the halfcaste population of the Northern Territory for the years 1934 and 1948 has therefore been taken for comparison:-

At first glance it would appear that the rate of increase in the European population exceeds that of the halfcaste and that no misgivings for the future of white settlement need be entertained. On the other hand, it must be remembered that the mixed blood increase is a natural phenomenon unaffected by migration and that the European figure has been very largely inflated by the current public works programme in the Northern Territory.

This inflation of the European population by impermanent influence is suggested by a study of the industry censuses for 1933 and 1947:

There has been no advance in primary production, a field of employment which alone can promise stable population in the Northern Territory. The overwhelming increase has been in those fields of employment directly and indirectly created by Government expenditure on public works which must be recognized as a transitory effect only.

The ratio of Group 4 to total population in 1933 was 1:7. On this basis, the increase of population in the 14 years to 1947 might have been expected to have increased this group by 885 – in fact the increase was only 618. With the ultimately inevitable reduction in public works therefore, to a “normal” level, the population of the Northern Territory might conceivably fall back to that of 1933 of even lower. The fall would be effected by European emigration. Halfcastes, it maybe supposed, would remain in the area. On this basis the mixed blood population, as estimated by the Native Affairs Department in 1948, would be to the European in the ratio of 1:1.5.

If official estimates are correct, they mean that the halfcaste population almost doubles every ten years. Increases in white population, on the other hand, are determined exclusively by greater expenditure of Commonwealth money on public works and administrative activities. In the absence of some unpredictable new stimulus to European migration, it is not inconceivable that within two decades the mixed blood will dominate considerable areas of the North.

The policies logical for Queensland were soon inadequate for the Northern Territory Administration and the native and mixed blood problems demanded attention as two distinct and unallied identities. In 1928 Mr. J.W. Bleakley, Chief Protector of Aboriginals in Queensland, after studying native administration in Central Australia for the Commonwealth Government, recommended the adoption there of the Queensland policy. Nevertheless, after pursuing his enquiries in North Australian and conferring with local officers, he withdrew this advice and endorsed the North Australian policy. This policy was based on the premise that in the national interest, the halfcaste must be raised to white status, proposed to be attempted in part by:-

- the removal of all mixed bloods from native camps and reserves;

- admitting all halfcaste children of lubras to homes to be reared and educated as white orphans, to European social and economic standards;

- training boys in trades to fit them securely for the assumption of full white citizenship at age 21 and to permit each at will with assurance and success to take his place as a social and economic unit in any part of Australia;

- full acceptance of the halfcaste as of European blood permitting the attendance of his children at public schools and extending to him all privileges and amenities appropriate to the European;

- educating girls in domestic refinement to elevate them to a standard qualifying their acceptance as white women;

- promoting the marriage of the excess female half-caste population to approved white men, thereby in some measure eliminating one social factor contributing to the breeding of halfcastes and stabilising the white population;

- the inter-marrying of mixed blood girls and boys with the purpose that the former might provide the latter with a stimulus to the attainment and maintenance of a higher standard of cultural and domestic life and thereby correct the prevailing trend towards reversion to native standards;

- the erection and furnishing for them of homes at accepted European standard under a self-aid housing scheme;

- prohibition of the marriage and stricter enforcement of the law against cohabitation between white and full blood.

Since the creation of the Department of Native Affairs in 1939 it appears that anxiety to release adult mixed bloods from the appearance of departmental control has led to their being prematurely cast upon their own resources. Simultaneously, some of the active measures of policy listed above have, possibly on ethical grounds, been discontinued. Today, even in Darwin and Alice Springs where the mixed blood native is immeasurably better situated than his brother in either Queensland or Western Australia, he is still confronted with a number of social and economic problems which are beyond his unaided ability to resolve. Careful thought must be given to the means whereby assistance may be preferred him without stirring resentment by the appearance of official patronage, racial discrimination or bureaucratic interference.

In Western Australia, as in Queensland, official policy originally did not differentiate between mixed and full blood natives. In the Kimberley, however, under similar economic and demographic influences to these operating in the Northern Territory, there developed a precisely similar situation. The white population was small, sparsely distributed and numerically static. The greater part of the native population was out of contact with European settlement, but tribes near townships gradually disappeared, to be replaced by a mixed blood community of high natural increase. Accordingly, about 1937, the Western Australian Department of Native Affairs, following the Northern Territory precedent, decided in favour of admitting halfcastes to full white citizenship. Execution of this policy, however, was not effected as in the Northern Territory by positive endeavour towards assisting and accelerating evolution. Full citizenship rights were proffered to these who could support an application for exemption with evidence of social advancement acceptable to a magistrate. In a region where the prevailing white standard or living itself was abnormally low and progressively trending towards determination by the coloured component of the community, it was inevitable that the threshold of admission to full citizenship should be set at ever lower levels. Latterly, the principal determiner of entitlement appears to have become the applicant’s ability to satisfy a magistrate that he may safely be trusted with the right to drink in hotel bars. Large numbers have been exempted who can by no measure of normal European living standards qualify for full white citizenship.

In few instances has been more self- respecting element of the white community suffered the halfcaste’s complete integration into white society. Notwithstanding that his wages are high, his standard of living is often extremely low. To provide a dwelling for himself and family, he must usually have recourse to improvisation from scrap material. Such structures are not permitted by law within the health area and he must therefore find a site beyond the limits of water, lighting, sanitary and communication services. These huts are ill-ventilated, over-crowded, unfloored, dark, dirty, unfurnish and inconvenient and provide no stimulus or facility toward greater cleanliness or comfort in one whose nurture has left him conditioned to a life of squalor. Deprived of water he cannot be clean either in his person or in his attire. Without a sanitary and waste disposal service the neighbourhood of his dwelling must become polluted to the detriment of his own and his neighbour’s health.

In Darwin and Alice Springs some special accommodation of improved type was long ago provided within the Health Area for a limited number of mixed blood families, but for some years no new work has been undertaken and a great number of these people must still live in improvised dwelling and camps.

Speaking generally, the mixed blood native has not been conditioned to self-supporting, productive enterprise. He is and always has been dependent upon wage employment for the rendering of a service. In the predictable event of the European’s displacement from the northern economy by an overwhelming coloured population the successful continuance of productive enterprise in this region will be jeopardised.

For service, the mixed blood worker may receive award rates of pay but his standard of living being so low, the wage is often excessive when related to his cost of living. Continuity of employment, therefore, is not important. Child Endowment brings him an income which further reduces the necessity for sustained occupation. Gambling and drinking provide him with both an escape and an outlet for his surplus funds and these, his apparent shiftlessness, the squalor of his dwelling and the dirt of his appearance, render him suspect to the white community. His friends amongst Europeans fall into two principal categories:-

- Philanthropic enthusiasts who can do little for him but preach a doctrine of brotherly love and equality which are not generally proffered or patient acceptance of earthly misfortune as a means to grace hereafter. This latter sentiment he sees dishonoured on all sides and often hears openly derided by others as his white associates.

- Those who preach the equality of man, a sentiment his Christian preceptors have implanted in him and the community of ownership which the cultural heritage of his native ancestors teaches him is proper and natural.

Ingeniously presented and misrepresented, Communist ideology must make a deep appeal to a people whose economic background is one in which the accumulation of private wealth is incompatible with human existence and to whom the foreign mode of life now thrusting inexorably upon them offers no present security or comfort and no promise of future dignified survival. It is inevitable that Communist influence must extend rapidly and effectually amongst these people while they continue outcast and this circumstance by aggravating the suspicious antipathy of the white race for them, contributes to perpetuation of the very conditions which must be removed if the march of sedition is to be halted in the national interest.

That the native, whether mixed blood or full blood, can in fact achieve and maintain a high standard of domestic comfort and refinement is amply evidenced by individual families in settlements as far apart as La Peruse, Mona Mona, Hope Vale, Darwin, Alice Springs and Broome. To achieve this standard, however, he requires assistance and encouragement such as is afforded him too rarely on missions and only exceptionally in the community at large.

His failure in the face of difficulties to him insurmountable, to maintain himself and his family at a reasonable standard of hygiene and domestic comfort, render him conspicuous in any well ordered community and inspired repugnance and revulsion in its more self respecting members. Unfortunately, this reaction which in the case of a European similarly situated would be directed towards the individual, in his case involves the group in a general disapproval.

In Queensland and Western Australia the remarks already made regarding the education of the native are applicable to the halfcaste.

In the Northern Territory children of mixed blood families living the general community are educated in the public schools. Orphans and the children of full blood mothers are accommodated on special settlements – Crocker Island and Garden Point – conducted for the Native Affairs Department by the Methodist Church and the Roman Catholic Church respectively. These institutions are rendering a valuable service in raising the status of these waifs towards qualification for full citizenship, but their work must be developed and improved. Not the least of the objections to the system are its insularity and its lack of promise for the future.