COMMONWEALTH OF AUSTRALIA

(CENTRAL AUSTRALIA)

OFFICE OF THE GOVERNMENT RESIDENT,

ALICE SPRINGS, 2nd September, 1929

His Honour,

The Government Resident,

ALICE SPRINGS

Your Honour,

I have to report that, acting under instructions received by telegraph from the Minister through His Honour the Government Resident, Darwin, I visited the Hermannsburg Lutheran Mission on Friday and Saturday, August 30th and 31st.

I found no evidence of Beri Beri amongst aboriginals at the Mission but 75 cases of illness were reported to me. Of these 75 cases, 37 have died, 18 are still under treatment and 20 have been relieved. From enquiries into the histories of the deceased and from examination of the patients, I am of opinion that all were suffering from Scurvy.

I examined all natives on the Station to the number of 161. As a result, I discovered that 9 of those discharged as relieved are still in a slight degree affected and that 33 hitherto regarded as unaffected show signs of incipient disease.

I drew up for the Superintendent, a complete list of articles of diet likely to be in use at the Mission and indicated the relative Vitamin content of each in respect of: Growth (A) Beri Beri (B) and Scurvy (C). This, if properly used, will enable the Superintendent to provide an economical and properly balanced diet and enable him from time to time to check the adequacy of his routine issues. I am forwarding herewith, for typing and transmission to the Chief Protector and to the Mission a brief statement of the cardinal symptoms of the various Vitamin deficiencies which, if intelligently used in conjunction with the schedule above mentioned, will provide sufficient information for the prevention of a repetition of the recent disaster.

I am given to understand that sufficient supplies of the nature required are now to hand or in transit and the crisis may be deemed to be passed. From inquiries made, I am of opinion that the outbreak was caused by faulty feeding, the result of lack of meat and plant food consequent upon the prolonged drought. I consider that the Mission has received very generous treatment and every practicable assistance from the local Administration and the transfer of Alice Springs aboriginals to the Mission in no way contributed towards or aggravated the circumstances which lead to the outbreak.

In the final analysis, responsibility for the outbreak rests upon the Mission authorities who have failed firstly to provide at the Station, now established over 50 years and founded as a permanent settlement, a water supply adequate to maintain a vegetable and fruit garden throughout the severest season and secondly in the absence of a local supply of fresh animal and vegetable food to provide imported substitutes.

In this connection it should be noted, however:

- that the Mission personnel was unqualified to recognise the nature of the disease afflicting the natives and made every effort to secure the services of a Medical Officer to advise on its prevention and treatment;

- that the Administration of Central Australia despatched a Medical Officer on April 20th 1929 when only 17 deaths from Scurvy had occurred and this officer appears to have failed to instruct the Mission Superintendent unequivocally as to the nature of the malady and the correct prophylaxis for it.

I recommend:

- that the Mission be required to provide a water supply in a suitable locality adequate to maintain a vegetable and fruit garden throughout the driest season or series of seasons;

- that a Medical Officer be appointed to Central Australia. The 37 deaths and the serious morbidity at the Mission are directly attributable to the lack of expert advice for the Mission Superintendent. It is no exaggeration to say that not one of those fatalities would have ensued had a Medical Officer with tropical experience been available at Stuart.

I am of opinion that the appointment of a Medical Officer to Stuart on the same salary and allowances as hold in North Australia will be more economical than the present system of bringing consultants from elsewhere and the removal of the sick to Adelaide Institutions for care and treatment that could be afforded locally. Particularly is this so in view of the now frequent visits of professional men from Adelaide who inquire closely into the condition of the aboriginal and then broadcast their impressions thereby, perhaps, stampeding the Administration into costly expedients.

Apart from this aspect, the provision of Medical service here would be good policy for the furtherance of white settlement.

It would not be possible for a Medical Officer in private practice to make a fair living without Government assistance. On the other hand, the principle of a part time Government Medical Officer in a district as sensitive to publicity and as subject to scrutiny and investigation by professional and semi-professional persons is a distinctly bad one. My impression of conditions here is that only discord and disorder would attend such an appointment unless the Administration was particularly fortunate in the selection of its appointee.

I recommend, therefore, that a full time Medical Officer be appointed as Chief Health Officer and Chief Protector of Aborigines. This Officer should be paid at the rate of £850 per annum rising by annual increments of £50 to £1000 per annum and he should have the right to retain fees for midwifery and major surgery only. In order that there be the closest co-operation between the two Territories in respect of Medical and Aboriginal policy, it is further recommended that this Medical Officer be attached to the North Australian Medical Service and in matters of Medical Policy subject to the direction of the Chief Medical Officer Darwin. By this means such disasters as that recently attending the visit of a Medical Officer inexperienced in Tropical Diseases to Hermannsburg should be avoided.

The seconding to Central Australia of a Medical Officer of the North Australia Medical Service will have the following advantages:

- It will provide the North Australia Medical Service with an alternative station thereby reducing the likelihood of monotony undermining efficiency;

- It provides the only method of ensuring uniformity of policy in two Territories faced by the same problems;

- It will ensure continuity of service. The North Australia Medical Service will be in a position to replace immediately any Officer who for any reason leaves at short notice. This would be utterly impracticable under any other system;

- Should an Officer otherwise sound, prove temperamentally unsuited to the district, it will not be necessary to tolerate him, as would otherwise be the case, for transfer could be arranged.

It will be necessary for the effective working of this plan that the Chief Medical Officer for North Australia be Gazetted Chief Medical Officer for Central Australia also. Ordinarily, the Medical Officer appointed to Central Australia would be directly responsible to the Government Resident of Central Australia but in matters affecting Medical Policy, transfer, leave and so forth, the Chief Medical Officer would be responsible.

Should the Minister approve, this matter may be promptly finalised. If applications are called forthwith for the appointment of an additional Medical Officer to North Australia, I will be able on my return to Darwin to second an experienced Officer to Stuart without delay.

(sgd) Cecil Cook

Chief Medical Officer for North Australia

PART II: EVENTS PRECEDING THE INQUIRY

The Finke River Lutheran Mission to the aboriginals was founded at Hermannsburg, 85 miles west of Alice Springs, over half a century ago. It has in the past successfully maintained a large herd of cattle, smaller herds of sheep and goats, a large vegetable garden and an orchard in which prior to the drought of 1890 grapes and citrus fruits were cultivated.

The Head Station is dependent for water upon four shallow wells formerly equipped with improvised windmills but now fitted with hand pumps. The water in these wells reaches a very low level during the dry season, and becomes scanty and brackish. The Superintendent states that at these times the water is unsuitable for gardening even were there sufficient of it. Another source of water supply is rainwater catchment from the buildings, a total area of some 2000 square yards which on the basis of an average annual rainfall may be expected to yield some 72,000 gal. per annum if sufficient storage tanks are provided.

In addition thee are springs at Koprilya, the Gilbert, the Government Camp, Ellery Creek, Palm Valley, and elsewhere, which provide water on the run at various distances from the Head Station.

Since 1925 when the last heavy fall of rain was recorded Hermannsburg has experienced a prolonged drought. Although good rain (4 inches) fell in April and May, 1926, the fall was so late in the year that the resulting growth of grass was promptly checked by the winter frosts. Since that time only scattered falls have been experienced. The monthly rainfall (points) at Hermannsburg during the past three years is shown in the subjoined table –

A total of 867 points for 32 months.

It is not surprising that the shallow wells with their tendency to salinity became inadequate for gardening during the winter of 1928 and no vegetables were available for consumption after October of that year. A further result of the drought was the reduction of the cattle herd from 3,000 head in 1926 to 200 at the time of this inquiry. It should be mentioned that other factors were alleged by the general public to have contributed towards this notable reduction.

The population of the Mission is under ordinary circumstances fairly constant. At 31st July it was stated to be –

During November 1928 there were 232 aboriginals on the mission. Ration issues made during his month were:

In addition, a fair amount of game and native foods was secured. There were two births at the mission during the month.

In December 1928, in order to remove all the idle aboriginals from the neighbourhood of Alice Springs before the formation of a railway construction camp there, the Government Resident arranged with the Hermannsburg Mission to receive all the old and infirm at that time being rationed in Alice Springs, on the understanding that they would continue to be fed and clothed at the expense of the Government. These aboriginals to the number of 78 were provided with rations for the road and set out for the mission on foot. After various delays due to illness, fatigue and laziness the natives arrived at Hermannsburg about 17th December, and were found to number 145, details being –

On being advised of the unexpected increase in numbers, the Government Resident authorised the mission to accept the additional natives on the same basis as those from Alice Springs. For the maintenance of these 145 aboriginals the Government Resident forwarded to Hermannsburg those supplies which ordinarily would have been issued to the camps in the vicinity of Alice Sprints. These rations consisted of flour, rice, sugar, tea, sundry medicines, tobacco and pipes. The mission stores were not to be affected by the advent of these aboriginals, who were to receive from Government supplies the following weekly rations, intended in common with all old and infirm ration issues solely as a supplement to native food –

| Flour | 4 lbs. |

| Sugar | 1 lb. |

| Tea | 2 oz. |

Shortly after the arrival of what now came to be called the Government camp, Mr. Heinrich, the Acting Superintendent, reported that everything was normal at the mission and that the new arrivals were settling down well to “Esshaus” Routine. It appears therefore that at this time supplies were pooled and all natives on the station received their meals through the communal kitchen. These meals took the form of a soup or stew to which the flour was added. A week later Mr. Heinrich reported that meat was no longer regularly obtainable and suggested the substitution of pearl barley. The stew was now replaced by a “flour soup” prepared by adding flour paste to boiling water on the basis of 1 lb. of flour to every five persons to be fed. The daily ration at this time was as follows:

Breakfast – Tea with sugar. Flour soup.

Lunch – Coffee with sugar. Flour soup with barley or rice added.

Tea – Tea with sugar: Flour soup.

A more monotonous dietary, it is difficult to conceive.

At the same time Mr. Heinrich reported that the station water supply was very unsatisfactory, both as to the quantity available and the quality of that obtained. Intestinal colic and diarrhoea were epidemic and barcoo rot was prevalent. The appearance of these diseases was attributed to the inferior quality of the drinking water pumped from the station wells.

During the latter part of December 377 natives were fed at the mission. For the month, ration issues were –

| Beef | 4,000 lbs. |

| Mutton | 210 lbs. |

| Flour | 7,033 lbs. |

| Sugar | 936 lbs. |

| Tea | 71 lbs. |

| Barley | 40 lbs. |

| Rice | 154 lbs. |

Game was available to supplement the mission rations.

There were three deaths amongst mission natives during the month – one adult from accident and two infants from pneumonia.

January 1929. For the first fortnight a little meat was available but for the remainder of the month there was none for general distribution. The mission was said to be destitute of game.

Towards the end of the month the Acting Superintendent reported that owing to the drain on the mission water supply resulting from the increased number camped at the station, the wells were failing. Dysentery and “other maladies” had become epidemic and the provision of some alternative source of drinking water was considered to be a matter of extreme urgency. It is not clear why the transference of the Government camp to another water was not seriously considered. In order to relieve the situation the Government Resident arranged to purchase and lend to the Mission.

1 strong camel and pack saddle at a cost of £8.

3 pairs of 30 gal. water canteens at a cost of £16.10.

The camel and gear were to be used to transport water from Koprilya Springs to the mission.

Under the date 28th January the Acting Superintendent complained that since the enforcement of the regulations prohibiting aboriginals from handling firearms or poison, able bodied natives on the mission were no longer able to secure game or dingo scalps. They were not fed by the mission and under these conditions were now unable either to procure food or to make money with which to purchase it. The Government Resident therefore approved of able bodied male aboriginals beings rationed by the same rations as the old and inform, were not to receive pay, and the issue was conditional upon the recipient working for the mission. Precisely what work was available for these natives is not stated; why there were not permitted in accordance with the regulation referred to, to carry firearms under licence is not clear, and why the mission which received the benefit of their work, if any, was not required to bear the cost of feeding them is a mystery.

Owing to the shortage of beef and the alleged absence of game, the Government Resident further authorised an increase of flour rations from 4 lbs. to 7 lbs. per week. During the month 383 natives were rationed, the issue being –

| Beef | 2,200 lbs. |

| Jam | 80 lb. |

| Flour | 9,922 lbs. |

| Sugar | 1119 lbs. |

| Tea | 139 lbs. |

| Barley | 180 lbs. |

| Rice | 184 lbs. |

There was no game to supplement the mission ration.

Two mission natives died during the month, one from dysentery and one apparently from malignant disease (cancer).

February On the 2nd February the Department of Home Affairs, having regard no doubt to the incidence of dysentery reported at the end of January, inquired by urgent telegram as to the necessity of despatching a medical officer to Hermannsburg. A reply was sent by the Government Resident in the following terms –

- A medical officer could do no more than was already being done.

- The outbreak of dysentery was due to bad water.

- Arrangements were complete for the transport of water from Koprilya Spring, five miles from the Head Station.

- The Acting Superintendent advised that since the provision of good water and the issue of bread in lieu of flour soup, dysentery had disappeared. The Government Resident therefore concluded that the outbreak was subsiding.

On 19th February, just three weeks after his securing the rationing of the male ablebodied, Mr. Heinrich requested a similar concession for the ablebodied lubras. The reason for the delay is not apparent. It appears that the working women had hitherto received from mission stores only 3 lbs. flour per week. In the absence of game and meat it was desired that the Government should increase this ration to 7 lb. per week. This was accordingly approved.

No mention is made in this communication of an impending shortage of supplies, yet in a report dated the following day 20th February, 1929, Mr. Heinrich advised that the Government Rations were exhausted. Arrangements were thereupon made by the Government Resident for the mission to ration the Government camp and the unemployed ablebodied natives from the mission stores pending replacement by the Government.

During the month 387 natives were rationed, the issues being –

There were one birth and four deaths during February. Of the deaths, two from the description of the deceaseds’ sufferings must have been due to scurvy though this fact was not recognised at that time.

No game was secure to augment the mission supplies.

March. As from 1st March the rationing system was changed. It was arranged that the mission should receive a lump sum of £580 computed on the basis of feeding 145 aboriginals from that date until 30th June, 1929, at a cost of 4/8 ½ per week per adult and 3/8 ½ per week per child. The rationing of ablebodied mission aboriginals was discontinued. The basis of computation was that submitted on 22nd January by Pastor Riedel on behalf of the mission.

Early in the month diarrhoea again became epidemic. Three natives died during the first week and on 8th March fifth were reported to be ill. The attendance of a medical officer was requested.

It was reported that stocks of flour were becoming low and that only one camel was available for the transport of water. By 14th March all rations were exhausted and the mission loading was still held up at Rumbalara, the poverty of the camels by which it was to have been brought to the mission rendering its transport impossible. There appears to have been no timely recognition of this possibility and no prompt action to anticipate it. In this emergency the Government Resident arranged on behalf of the mission for the despatch of supplies from Alice Springs.

On 23rd March an inquiry was held by Donald Campbell Esq., J.P., into the deaths of ten aboriginals at Hermannsburg. In the course of his finding the coroner expressed the view that at least one of these deaths was due to scurvy.

On 26th March, Pastor Riedel, in a telegram requesting a renewal of the unemployed dole previously supplied to ablebodied mission aboriginals, mentioned that prevalence of a ‘mysterious disease’ which had caused ten deaths since 10th February.

In his reply to this telegram the Government Resident stated that it was proposed to make £125 available in return for road work to be performed by mission labour. He added that in view of the difficulty attending the maintenance of an adequate supply of pure water at the head station, Mr. Albrecht, who had now resumed duty as Superintendent, had been advised to remove the camp to water elsewhere on the Finke River.

386 aboriginals were rationed during the month, issues being –

No game was secured.

There was one birth during the month. Deaths totalled nine – six mission and three Government aboriginals. All the deaths were directly or indirectly due to scurvy though the fact was not at that time realised.

April. Following a belated realisation that aboriginals may carry firearms under licence, this means of securing additional fresh meat was utilised during the month. Considerable difficult in securing stores was experienced. Eventually a motor truck was utilised to transport the stores and the first small load arrived in the middle of the month.

On the 21st April, E.J. Howley, L.R.C.P., visited Hermannsburg by arrangement and at the expense of the Government. He reported to the Government Resident that –

- There were at the mission a large number of cases closely resembling beri beri.

- The main article of diet seemed to be a kind of soup made from flour.

- There was a lack of fresh vegetables and milk for babies and younger children.

- He recommended the substitution of rice for flour and provision of milk fresh or canned.

- There had been twenty deaths.

- In his opinion such herding of aboriginals under artificial conditions was undesirable.

- He recommended the appointment of a trained nurse to Hermannsburg.

He further advised that he had instructed the Superintendent to give rice and peas to sufferers of beri beri instead of flour, and to feed infants with condensed milk. Every morning the sick were to receive boiled split peas which had been soaked overnight, at midday rice or sago, and at night a piece of bread with tea. Lard and game when procurable were also given.

In a letter dealing with this period but dated 22nd May Mr. Albrecht reported that many natives were leaving the station on account of superstitious dreads connected with the outbreak of beri beri, and for other reasons. Some he stated had gone to the vicinity of the railway construction camps at Maryvale, others to big corroborees on the Finke and Hugh Rivers. “Nearly 70 have left, only a few men and most of the women of the Alice Springs old and infirm remaining”. He expressed the opinion that others would also go and asked from some measures of compulsion to ensure the others remaining.

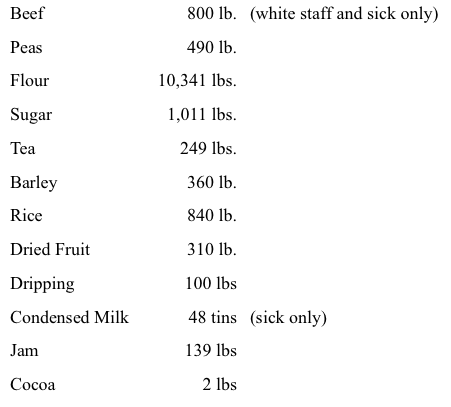

375 natives were rationed during the month, the issues being –

The dripping, fruit and tinned meat were issued during the last week of the month only, the dripping being boiled into the flour soup.

There was one birth during April. There were ten deaths including two Government aboriginals. In reporting the deaths Mr. Albrecht noted that only one was due to beri beri. This is in conflict with Dr. Howley’s report to the Government Resident. In the light of investigation made in the course of this inquiry it appears that nine of these deaths were due to scurvy.

May. The remainder of the supplies were received from Rumbalara about the middle of the month.

There were two births and two deaths amongst mission aboriginals during the month. Only one of the deaths apparently was due to scurvy.

349 natives were rationed, issues being –

Game was fairly plentiful.

June. There was one birth in June. Two mission natives and one Government camp died, at least two of these deaths being due, as now appears to scurvy.

332 aboriginals were rationed. It is difficult to understand how this figure was reached. At the end of January there were 383 aboriginals on the mission, including some 145 maintained by the Government. According to periodic reports from the mission some 90 of these were removed by death or migration before the end of May. There should therefore have been only 293 natives on the mission books during June, the reduction being mainly in the numbers in the Government camp. No adjustment however was made in respect of this reduction. Presumably therefore some 40 new arrivals at the mission had taken their place on the Government ration list in lieu of those who had gone. There is however no record of any authority for this procedure.

Rations issued during the month were –

Game was fairly plentiful.

During July 325 natives were rationed, issues being:

There were two births during the month. Of these infants one died aged eleven days. There were seven other deaths, all directly or indirectly due to scurvy – then unrecognised. Only one of them was from the Government camp.

For the new financial year it was agreed that the mission should continue rationing old and infirm aboriginals for the Government, for which payment at the rate of 4/8 ½ per week for adults and 3/8 ½ per week for children would continue to be made. The mission for its part was to furnish a return of aboriginals so rationed month by month, and the amount of reimbursement was to be reviewed in the light of cheaper freights after the opening of the Alice Springs railway.

In addition £100 was granted to the mission for the performance of roadwork on behalf of the Works Engineer and a special grant of £250 per annum was made in consideration of the difficult times through which the mission was passing.

August. There was one birth in August. There were five deaths, all from scurvy. Figures as to ration issues were not available at the time of this inquiry.

The Chief Medical Officer of North Australia visited Hermannsburg on 30th and 31st August in order to inquire into the outbreak of disease there.

PART III: Critical discussion of the ration issues

The ration issues of the mission require investigation from three standpoints, viz.The mission’s discharge of its obligations to the Government Resident in respect of the issue of rations supplied or paid for by him.

(1) The mission’s discharge of its obligations to the Government Resident in respect of the issue of rations supplied or paid for by him.

(2) Their adequacy or otherwise in respect of the basal food factors.

(3) Their adequacy in respect of vitamin content.

- As to the conformance with contract. During the period 17th December to 28th February rationing was effected under an arrangement whereby the Government Resident supplied the necessary stores and the mission was entrusted with the responsibility of issuing them on a scale prescribed by him. Up to 28th February 1929 the Government Resident had supplied to the mission and the mission claimed to have distributed:

During this same period the Government resident had ordered distribution on the following scale:

These figures are only approximate, but they serve to indicate that issues actually made by the mission were in general accord with the Government Resident’s authorisation. It is necessary to establish however that pari passu with these distributions of Government stores the ration issues to mission aboriginals proper were maintained at their former level, for in the pooling of stores any reduction in this direction would indicate that Government stores supplied for a specific purpose had been diverted to mission use.

During November 1928 before the arrival of the Government camp the weekly ration issue made by the Superintendent was:

Assuming that issues made during the first seventeen days of December conformed to this standard, the issues to mission aboriginals subsequently to the arrival of the Government camp may readily be calculated.

In respect of the staple food, flour, then, there is no justification for supposing that the mission reduced its own use concurrently with the distribution of Government stores. Sugar and tea do show a reduction as compared to November but this may have been due to other causes, and in any case there is no ground for accepting the November issue as an arbitrary standard.

For the month of February issues were.

Here it is difficult to avoid the conclusion either that:

(a) after the arrival of the Government camp mission natives received a ration markedly inferior in respect of its sugar and tea content to that formerly issued; or

(b) in the pooling of supplies the mission authorities tended doubtless unwittingly to take advantage of Government issues of sugar and tea to reduce the issues of those commodities from the mission stores.

For the remaining 17-1/3 weeks of the financial year 1928/29 the mission was required to ration the equivalent of 116 adults on the scale of : Flour 7 lb., sugar 1 lb., and tea 2 oz., per week. This would require a total issue for the period of the order of:

For this period the issue by the mission totalled

So that there remained for issue to mission natives proper

a weekly rate of

For the part of this period, April and May, mission stores were extremely low owing to the failure of carriers to lift the loading from Rumbalara. The figures as they stand indicate that either

- the mission natives did not receive additional flour in lieu of the meat no longer procurable;

- natives in the Government camp did not receive the stipulated ration but shared it with the mission aboriginals.

The flour ration has increased conformally with the additional issue in lieu of meat. Tea was supplemented by coffee. Sugar however is unusually low.

- As to adequacy. Unfortunately although the mission has kept detailed records of its issues the extraction of information as to the allotments made to the Government camp as distinct from the mission is impracticable. For part of the time supplies were pooled.

Two methods of examining the adequacy of the ration issues are available:

(a) To assume that the Government camp received in full the issues ordered for it by the Government Resident. For any inadequacy in this diet the Government would be directly responsible.

(b) To assume that all supplies were pooled and that mission and Government aboriginals alike shared equally in the issues. For any inadequacy in this diet the mission must accept responsibility.

(a) The Government ration. The rationing of old and infirm aboriginals is intended to provide sustenance for those aboriginals who through age or infirmity are no longer able to earn a livelihood in a civilised community or to maintain themselves in native fashion. Even these however are usually able to collect a certain amount of vegetable and animal food in the vicinity of their camps and they also receive food from their more active friends and relatives. The Government ration therefore is determined on the basis of the minimum sufficient to maintain life in idleness – the sustenance ration. The sustenance ration of the aged contains 15% protein and carbohydrates and a little more fat than that for the adult. It is held to be:

The percentage of each of the basal food factors contained in various articles of diet in use of Hermannsburg are tabulated in Appendix 1. From this one can ascertain that the value of the original diet issued to the Government camp was:

The diet originally prescribed by the Government Resident was therefore adequate as a sustenance diet, the deficiency in fat being met by excess of carbohydrate. It should be remarked however that is an ill-balanced diet, prolonged subsistence upon which unless supplemented is likely by reason of its low fat content to be followed by malnutrition and predisposition to respiratory disease and tuberculosis, and to symptoms of Vitamin A deficiency. It is moreover a diet lacking in staying power and by reason of its reliance upon vegetable protein, unfit for the young. Inasmuch as it was the intention that this ration should be supplemented by native foods it may be regarded adequate for its purpose. Unfortunately no game was provided to supplement it.

The diet formula intended to be adopted from 1st March was a good one, containing sufficient fat and more protein than was theoretically required. Part of this protein was supplied by meat and the ration therefore was designed with a margin to compensate for the biological inadequacy of the vegetable protein which had rendered the previous issue unfit for the young and for the worker.

The basal food factors of this diet were represented thus:

Unfortunately meat was not available and the flour ration was increased in an endeavour to make good the deficiency. The amended ration had the following values:

It was upon this diet that the Government Resident stipulated that ablebodied recipients should work, and this at a time when there was no game to supplement it. The minimum ration scales for light and laborious work respectively are:

The low protein in the ration therefore would have been too low even were it of animal origin. Being wholly vegetable its inadequacy in a diet for a worker was exaggerated. The deficiency of fat in this and earlier rations was likely to be reflected in a tendency to gastro-intestinal disturbances, malnutrition, pre-disposition to respiratory disease, and a high infant mortality It is notable then that there were three outbreaks of gastro-enteritis during this period, and that the infant mortality rate was 92 per 100 live births.

(b) The pooled ration. To arrive at an approximation of the ration issue per native per day on the basis of the pooling of supplies, is a somewhat difficult matter. To do so it is necessary to assume:

- That the rations issued by the mission were divided equally amongst both mission and Government aboriginals.

- That the number of aboriginals stated by the mission to be have been rationed each month is correct for the whole month.

- That the ration of adults to children remained constant.

At the outset the mixed population must be reduced to terms of adult males. This figure may be termed the adult equivalent, and it is determined on the following basis: The adult male is taken as the unit. An adult female and a child of fourteen years are estimated each to consume 7/8th of the food required by an adult male. A child of ten years requires about one half as much as a woman.

From details of the constitution of the population at 31st July, 1928 it is estimated that the adult equivalent at Hermannsburg is represented by 4/5th of the total number of aboriginals listed in any month. Utilising this figure it is possible from the monthly statement of ration issues to determine approximately the amount of each foodstuff that an adult would have received daily from the pooled resources of mission and government. In the following table are set out details of daily adult ration during each month of the period under review. Females would receive seven-eighths and children about seven-sixteenths of the stated quantities.

X supplemented by game.

The protein ration was adequate until May only.

Throughout the ration period, and until dripping was incorporated in the flour soup in June, the fat issue was inadequate. Insofar as fuel value is concerned, the deficiency was made good by increased carbohydrate. In so far as adults were concerned, this lack of fat was liable to produce intestinal disorders, and in nursing mothers poverty of the lacteal secretion. Children and infants however were exposed to the risk of malnutrition, respiratory disease and gastro-intestinal disturbances. Consequently it is not surprising to find that

(a) Diarrhoea was epidemic in December, late in January, February and March, when fat was low, ceasing with the resumption of game hunting in April.

(b) Although the infant mortality of Hermannsburg is usually high, presumably on account of incorrect feeding, it was exceptionally high during the period under review.

During this period the following deaths in children aged two years and under were recorded.

The infantile death rate for the period was 92 per 100 live births, compare with 44.5 for 1927, and 43 for 1928.

3. As to vitamin content

(a) Vitamin A. Effective vitamin A deprivation may be said to have commenced during the second period of January with the cessation of the meat ration. In Appendix 2 the vitamin contents of various foodstuffs in use at the mission are set out. Reference to this table will show that of the rations issued between November and April only the beef provided a source of vitamin A. With the cessation of the beef issue in January the general diet scale made no provision for this vitamin, but with the resumption of game shooting in April this deficiency was probably made good.

No illness attributable to deficiency of vitamin A was observed at Hermannsburg in August and none was recorded as having occurred. Possible its ill effects would have been manifest in infants but for the early death of most of them from other causes. Those of more mature years safely traversed the period of deprivation by drawing upon the body reserves which would be stimulated moreover by bright sunlight. It is important to observe however that after this period of deprivation reserves must be low and it is improbable that the little game available, though retarding it, will be adequate to prevent further reduction. If this fat deficient ration is maintained therefore the appearance of Vitamin A deficiency disease must be expected.

(b) Vitamin B. The only sources of this vitamin in the diet on issue in December were beef and barley. With the termination of the beef issue the barley ration itself much more potent than beef in respect of vitamin content was increased.

Notwithstanding Dr. Howley’s statement that he saw cases of beri beri at Hermannsburg in April, no evidence of its occurrence there was found during this inquiry, but on the contrary cases diagnosed by him as suffering from beri beri were found to be affected with scurvy. On the whole it may be confidently asserted that beri beri did not occur, at any rate in adults, at Hermannsburg during the year, and this is probably attributable to the agency of the barley ration. It must be remarked however that the barley ration was very low and some cases of beri beri would possibly eventually have occurred but for the additional vitamin B made available in April by the inclusion of game and peas in the issues.

(c) Vitamin C. With the cessation of the vegetable supply in October, sources of this vitamin were considerably reduced. The failure of the meat ration in January removed the only remaining source, itself inadequate. No food containing Vitamin C was included in the ration between this date and April, when peas were introduced into the diet. Even then, the method of cooking the peas was calculated to destroy the vitamin completely. Vitamin C as already noted is unstable to prolonged heating. At the mission the peas after soaking all night were boiled all morning and then added to the midday issue of flour soup. Theoretically very little if any vitamin C can have survived this preparation.

Scurvy may be expected to appear in man after from four to eight months’ deprivation of vitamin C. There having been practically no vitamin C in the mission dietary since October 1928 an outbreak of scurvy was to have been expected late in February and in March. Premonitory outbreaks of gastro-intestinal disturbance have already been considered. At Hermannsburg the first cases of a “mysterious disease” now definitely known to have been scurvy appeared towards the end of February and were associated with four deaths. By 8th March some fifty aboriginals were afflicted and three more had died. The disease was accompanied by dysentery and was at first regarded as a recrudescence of the enteritis previously attributed to the drinking of impure water.

From detailed inquiry it was learned that characteristic features of the malady were swelling and bleeding of the gums with loosening and sometimes shedding of the teeth, swelling and crippling of joints, usually the knees or ankles, which were fixed in flexion and exquisitely tender, emaciation, haemorrhages and commonly death after weeks of suffering. Certain of the deaths were due directly to the malady whilst other fatalities resulted indirectly in infants who were being nursed by scorbutic mothers. Practically all the patients were stricken down in February, March and April, those examined in August being survivors from that time. Details of the deaths are given in the following table:

At the time of this inquiry there had been 75 recognisable cases of whom 37 had died, 20 had been discharged, and 18 were still afflicted. All natives on the mission were medically examined and it was found that 33 up to that time believed to be unaffected showed slight signs of disease whilst 9 of those previously discharged were still to some degree affected.

A critical analysis of the incidence of the disease reveals the following:

Owing to the fact that whilst all available mission natives were inspected, very few Government natives were presented for that purpose, the percentage 10.5 may not give a true indication of the incidence of disease amongst the latter. Nevertheless the death rate and current affection serve to indicate that the incidence upon natives in the Government camp was much lighter than it was upon those of the mission. This circumstance may have been determined by one or more of a variety of factors:

(i.) The onset of scurvy is accelerated by the performance of manual labour. Those in the Government camp were not required to work. Amongst mission aboriginals the incidence upon various age groups was as follows:

The greatest incidence was amongst the young. The rate amongst infants is exaggerated by the effects of inanition due to improper feeding, nursing mothers being unable to nourish their offspring by reason of the poor quality of the milk secreted in the low fat ration. Recognising this factor of exaggeration in the infantile groups, the heaviest incidence may be said to have fallen upon the school children and the ablebodied – those of whom a certain amount of routine work was required. That the ablebodied seem to have been less heavily involved than the school children is due to the comparative immunity of males, a number of whom were for lengthy periods camped on the run away from the station and for whom a limited quantity of fresh food in consequence occasionally available. This comparative immunity of males is revealed by the figures of incidence upon the sexes – Adult males 24%, adult females 51%. The effect of work upon persons receiving the station ration is made the more apparent by the incidence upon female adults.

(ii.) Natives in the Government camp were free to hunt in the native style and were expected to eke out the official ration with such native foods as parakylia, wild onion and so forth. Moreover, after April these natives were no longer required to attend for meals at the kitchen but were given one week’s supplies in advance and sent into the bush to fend for themselves until the next ration issue became due.

The native foods which they in consequence secured were doubtless able to provide them with a source of Vitamin C sufficient to prevent the onset of scurvy. An interesting point obtrudes in this connection. After the Government natives were encouraged to leave the mission for short periods, no cases of scurvy were reported amongst them. Whilst they were camped at the mission prior to April 1929 most of the foraging for native vegetable food would as usual be done by the lubras, and it may be that there was a tendency amongst the men to avail themselves fully of the official ration issues, leaving the lubras to eke out the remainder with the native foods they had succeeded in collecting. The incidence of scurvy then upon males in the Government camp was 15% and on females 6.6% whilst 100% of the male cases and only 40% of the female cases were fatal.

(iii.) The Government camp at Hermannsburg was seriously depleted in April. Many left the neighbourhood of the mission owing to a superstitious dread engendered of the outbreak of disease and its heavy mortality. It is possible therefore that cases of scurvy sufficient in number materially to affect the quoted incidence may have been overlooked in consequence of this migration. Serious cases however could not have been moved, and subsequent events have shown that once the natives left the mission and returned to their normal mode of life incipient scurvy amongst them was arrested. It is probable therefore that the figures quoted for deaths and severe cases give a true indication of the relative incidence of the disease upon mission and Government aboriginals. It is regrettable that detailed returns of these migrations were not furnished by the Superintendent for their absence renders it difficult to estimate the significance of the quoted figures, and impedes any attempt to check the ration issues made on behalf of the Government.

Notwithstanding that the nature of the disease and the steps to be taken for its alleviation were indicated in March by Mr. Campbell, no article of diet containing vitamin C was provided until 23rd April, when the ration of peas ordered by Dr. Howley as preventative of beri beri was included. Although this was prepared in such a fashion as to warrant the expectation that all the anti-scorbutic factor would be destroyed, it is a notable fact that its inclusion was sufficient not only to prevent severe manifestations in new cases but in association with a small supply of condensed milk to relieve some of those already affected sufficiently to warrant their discharge as cured. The results of laboratory experiment are definitely contrary to such an outcome, but this field experiment on the large scale must be accepted none the less.

In August, Dr. J.B. Cleland who was visiting the mission ordered citrus fruits and swedes to be given both as prophylactic and as a cure. These were not available in sufficient quantities until September but enough were procured to relieve the position. After this inquiry the Superintendent was provided with a schedule of foodstuffs in common use in which the value of each article in respect of its vitamin content was clearly indicated. Instructions were also given as to the symptoms of the different vitamin deficiencies.

One other matter calls for mention here. Although the mission has been in existence for the many years, and although its history shows that practically every month has taken its toll in death from curable disease and that severe epidemics of infectious disease are unusually common, nevertheless no hospital accommodation of even the most elementary character has been provide. During the outbreak of scurvy most of the sick were left in their huts and wurlies to the care of their fellows. It was a common experience, according to the Superintendent, to find that after a brief period of nursing the aboriginal abandoned his patient to his fate. Some of the worse cases and those sleeping in dormitories and huts where no nursing attention was forthcoming were removed to small ill-ventilated huts near the Superintendent’s quarters. There they lain in their agony in numbers far too great for the capacity of their quarters, and their sufferings were materially increased by the hardness of the floors on which they lay and by the pollution of the stagnant air with the acrid smoke of the fires maintained inside the huts to provide some measure of warmth.

CONCLUSION:

- A severe drought has been experienced at Hermannsburg since 1926.

- Owing to inadequate water supply this drought has created serious difficulties in the feeding of aboriginals.

- In December, 1928 the mission undertook to feed on behalf of the Government Resident 145 old and infirm natives. The necessary stores were provided by the Government until 28th February. Thereafter the mission was paid on per capita basis.

- The diet prescribed by the Government Resident was adequate in its content of basal food factors for the purpose intended, viz. a sustenance ration for aged and infirm.

- In January the Government Resident approved of unemployed ablebodied mission aboriginals being rationed from Government stores on the same basis as the old and infirm provided that they worked. There does not appear to have been any reasonable obligation upon the Government to ration these natives.

- In January owing to the failure of the meat supply the Government Resident increased the flour ration. This diet scale whilst deficient in fat was adequate as a sustenance ration for the aged and inform who could supplement it with native food, but it was not adequate for the performance of work and this stipulation in respect of the ablebodied should not have been made. In consequence of it, natives who could at large provide themselves with a superior ration were induced to remain at the mission and were deprived owing to the performance of work from any opportunity of hunting. There were therefore compelled to work upon inadequate ration. The rationing of ablebodied mission aboriginals was a mistake and the requirement that recipients should work was unjustifiable.

- Owing to the pooling of supplies it is difficult to ascertain how effectively the mission discharged its obligations. If Government stores were issued strictly according to the Government Resident’s instructions, then the mission aboriginals proper during this period received a daily ration inferior to that issued prior to the arrival of the Government camp. Alternatively all natives on the mission received a similar ration and in that case Government supplies of sugar and tea were used to eke out mission supplies.

- It is difficult to check the number on Government rations. The total population of the mission on 31st July 1929 was stated to be 325, including 213 mission and 112 Government aboriginals. At the muster on 31st August only 161 were present, these being primarily mission blacks. In December 1928 there were 358 aboriginals on the books, including 145 Government. Between that date and 31st August, 1929 there had been an excess of deaths over births of 34, and 70 were stated to have left the mission as early as April, 1929. There should therefore have been at most 254 natives on the mission at the time of the muster. If the mission figures are accepted, and there is no reason for doubting the Superintendent’s sincerity, new arrivals must have been included upon the Government ration list. No authority for this procedure can be found.

- An outbreak of scurvy occurred at Hermannsburg in February and March, 1929. The outbreak was due to the issue of a ration deficient in Vitamin C owing to an entire lack of fresh meat, fruit and vegetables.

- In final analysis, drought conditions were responsible for this lack of fresh food, but the situation was aggravated by:

- the absence of a garden at the mission;

- the cessation of game hunting;

- the detention of natives around the mission instead of permitting them to leave.

The outbreak was in no way attributable to or aggravated by the transfer of the Government camp from Alice Springs.

- (11)As early as 23rd March when only ten deaths had occurred the necessity of providing a diet of fresh fruit and vegetables was indicated by the Coroner. No action was taken.

- (12)The incidence of the disease was heaviest upon the mission natives and amongst those upon the ablebodied required to work. The disease was lightest in incidence upon the Government camp who by reason of unemployment and independence of habit were able to supplement their ration issue with fresh native food. These facts show that there is a moral obligation upon any mission which disturbs the natural life of the aboriginal to substitute an adequate and well balanced diet for that of which he is deprived by the new order of living.

- (13)A high infant mortality has obtained at Hermannsburg for some years. Dietetic errors are probably responsible.

RECOMMENDATIONS:

- The maintenance at Hermannsburg of old and infirm aboriginals on behalf of he Government should be discontinued.

- Any financial assistance to the Hermannsburg mission should be made conditional upon:

- the prompt provision of a water supply capable of maintaining a fruit and vegetable garden throughout the driest season.

- the immediate erection and furnishing of a well lighted and ventilated hospital.

- the prompt notification of disease in aboriginals at the mission; this notification which should be accompanied by a full clinical description of the case should be forwarded to the Medical Officer, Alice Springs.

- A medical Officer experienced in tropical diseases and diseases of Australian aboriginals should be appointed to Alice Springs. This Medical Officer should be an officer of North Australia Medical Service and under the direction of the Chief Medical Officer, Darwin.

- Under the supervision of the Medical Officer, the mission should be required to issue a properly balanced and adequate ration, sufficiently rich in vitamins.

- The Medical Officer should commence as soon as possible as investigation into the causes of the high infant mortality at Hermannsburg during recent years.

It is desired to state, in concluding, that whilst it is thought that the Acting Superintendent found himself embarrassed by and unable to cope with the grave developments which had so quickly succeeded one another during his period of temporary responsibility, and that he was in consequence too prone to rely upon Government assistance and advice for the solution of problems properly his own, it is felt that both he and Mr. Albrecht conscientiously endeavoured to discharge their obligations to the Government and to the aboriginals in their care, under very distressing and difficult circumstances and with facilities which after half a century of mission work can only be regarded as disgraceful, but for the deficiencies of which they personally are in no way responsible.

(sgd) Cecil Cook. M.D., D.T.M. and H

Chief Medical Officer

North Australia.