by C.E. Cook, M.D., Ch.M., D.P.H., D.T.M. & H

A paper delivered at the Commonwealth Conference of the BMA, Brisbane, May 1950

The region with which this study is concerned includes roughly that portion of Australia lying north of the 19th parallel of South Latitude and embracing the Peninsula and Carpentaria Divisions of Queensland, the northern third of the Northern Territory and the Kimberley Division of Western Australia.

With an area so extensive, it is impossible, with uniform accuracy, to reduce a description of its physical and demographic features to general terms. Subject to this disclaimer to precision, the terrain may broadly be considered as comprising a coastal plain of variable depth backed by a tableland rising abruptly as a bastion close to the eastern sea board and falling gradually in elevation to westward.

The coastal strip is highly fertile east of the bastion. To the north and west, however, it consists of poor class forest country, intersected by numerous tidal estuaries and, in the areas of higher rainfall, broken up by swamps.

The tableland in the east is heavily timbered with rain forest and jungle but on the western watershed it consists of light forest and savanna downs. Mineral deposits of gold, tin, copper, lead, iron and tantalite are widely distributed through these uplands. Those particularly affecting settlement lie dotted along the eastern bastion throughout the length of Cape York Peninsula as far south as the Cairns hinterland, on the Gulf watershed, along the Northern Territory Railway and in the Halls Creek and Derby areas of Western Australia.

The southern half of the coastal strip east of the bastion has a high rainfall, the annual average ranging in different localities from 60” to 120”.

If this sector be excluded, the rainfall for the region may be conveniently delineated by a series of parallel isohyets, progressively diminishing by 10” annually from 60” along the northern coast to 20” along the southern limit.

The climate is monsoonal – a hot, wet monsoon from November to March and a dry, cold monsoon from April to October. During the wet season water courses become rushing torrents and extensive areas of level ground, particularly in the coastal plain, are inundated. There occurs a prolific growth of herbage which in the coastal plains is rank and valueless but attains a height of up to 10 ft.

With the south-east change in April or May, drying is rapid. In the coastal plains the inundated areas contract to permanent reed-bordered lagoons and water courses become saline for many miles from the sea. Grass fires rage through and completely destroy the rank wet-season growth, leaving the surface of the earth parched and devoid of herbage, except in damp localities where less exuberant new growth occurs. On the uplands, water courses run dry and early in the dry season consist only of sandy or rocky channels in which the water rapidly contracts to temporary or permanent pools at long intervals, the sparsely timbered and lightly grassed high ground between becoming parched and dusty.

Before white intrusion during the latter half of the nineteenth century this region was exclusively inhabited by aboriginals. Their number is unknown and estimates are wholly conjectural. Considering their mode of life and known distribution since white settlement it probably did not exceed 100,000 and was probably much less.

Their only known contact with the outside world was that afforded by the transient seasonal visits of Macassars from the Celebes who came down in proas trepanging during the dry season to the northern coast of Arnhem land and the Gulf, establishing camps at certain favoured sites to set up their curing depots. This trade, which had endured for centuries, ceased in 1904.

Any study of the endemicity of disease here must be preceded by some account of the normal mode of life of this primitive people.

The native Australian practiced no agriculture nor animal husbandry; he domesticated no animal except the dog, established no village, built no dwelling, wore no clothing and acquired no property. Small property groups carrying practically no impedimenta except their primitive weapons moved as hunters over relatively extensive but definitely delimited, and for the most part tribally exclusive areas, living wholly upon the natural fauna and flora of the virgin bush. Stay in any camp was transient and its duration determined by the seasonal prevalence of game and vegetable food, the adequacy of water or the ceremonial requirements of tribal custom. Contact between families of the same tribe was of course frequent and on occasion sustained, contact between adjacent tribes occasional and transitory, even to the extent of successive occupancy of the same camp site.

No permanent dwellings were erected at those camps. The native slept on the ground in the shelter of the trees or in the dry bed of a water course. For any length of stay in the dry season he erected a simple windbreak of brush, grass or bark to leeward of which he lay with his family and his dogs round a small fire. In the wet season a shelter of similar materials afforded protection from the rain. The basic principles of sanitation were unknown and no conscious hygienic precaution in the disposal of wastes or excreta was practised. The native lore comprehended no conception of communicable disease whether food-, water-, air-, or insect-borne, or transmissible by contact. Indeed, it may reasonably be surmised that his lonely, migrant existence in an environment characterised by bright sun light, extreme of temperature and a seasonal succession of flood, fire and drought, supplemented by an effectual if undesigned intertribal quarantine would eventually have permanently eliminated most of those infections which for generations have plagued the more static peoples of the human race settled in fixed communities in association with herds of domesticated animals and amidst the accumulated by-products of human and animal existence.

Development of Australia’s north was first attempted as a defence project. In 1825 the British Government established a military and convict settlement at Fort Dundas at Melville Island. The settlement was in constant conflict with the hostile natives and suffered seriously from disease, including “fever”. The settlement was transferred in 1827 to Raffles Bay on Coburg Peninsula and finally abandoned in 1829.

In 1837 another effort to settle the north was made with a military and trading post at Port Essington. This was also a failure and was abandoned in 1849.

No further attempt at settlement was made for 15 years, when following Burke’s favourable account of the Gulf country (1861) and Start’s glowing reports upon the terrain traversed in his overland journey from Adelaide to Port Darwin, interest revived.

In 1864 a pastoral settlement of Europeans was established at Burketown on the Gulf of Carpentaria, the vanguard of a great pastoral migration from Southern Queensland and New South Wales northward and westward to the new pastures. This migration reached its zenith during the eighties when it extended across the Northern Territory to the Kimberleys.

In 1863, the South Australian Government established a settlement near Port Darwin and in 1870 work was commenced on an overland telegraph line to Adelaide. This line was completed in 1872, the Newcastle Waters section of it having been supplied from a base at O.T. on the headwaters of the Limmen River which flows into the western shore of the Gulf of Carpentaria.

In 1874 work was commenced upon the construction of a railway from Darwin to Pine Creek, this being the first section of a proposed trans-continental route to Adelaide. Some thousands of Chinese coolies were imported in this and the following years to serve as a labour force for this project and later to work in the gold fields discovered in 1876 in the Pine Creek area.

Gold was discovered in 1869 on the Gilbert River at Georgetown and in 1873 on the Palmer in Cape York Peninsula. To serve the sudden accretion of population in these areas and new fields adjacent, ports were established at Cooktown and Cairns (1876). The timber wealth and rihk soil of the Cairns area assured its prosperous development, notwithstanding the early decline of the gold fields which had called its settlement into being. Large number of Melanesians were imported to work in the banana and sugar cane plantations round Cairns during the seventies.

In 1879 Forrest reported the discovery of rich pastoral country along the Fitzroy River (W.A.) and during the eighties the great cattle movement from Queensland extender thither.

In 1886 the discovery of gold at Halls Creek in this vicinity led to a minor rush.

It is not necessary to detail the subsequent history of the region – development proceeded with the progressive expansion and increasing intensity of pastoral settlement, the establishment of port and administrative hamlets on the adjacent coast and the waxing and waning of mine fields of major and minor importance. Three dates of Northern Territory development are, however relevant to later discussion – Umbrawarra tin field rush 1908, Pine Creek-Katherine railway extension 1916-17, Katherine River Bridge and Birdum railway extension 1925-30.

Over most of the area development has not realised its early promise. The total population today, exclusive of aboriginals is 86,240 by no means evenly distributed. The Queensland section carries 78,440, the great bulk of this number occupying the rich agricultural belt along the eastern sea board round Cairns.

The population of the Northern Territory section is 5,000 of which a substantial proportion lives in the port and administrative centre of Darwin and in hamlets along the Northern Territory railway to Birdum. The coastal plain is practically unoccupied except for scattered missions, the rural population being widely distributed through the pastoral belt of the tableland in cattle station homesteads from 50 to 100 miles apart.

The population of the Kimberleys is 2,800. As in the Northern Territory, so here, the coastal region is unoccupied except for small hamlets at the ports of Wyndham, Derby and Broome and several missions. The pastoral settlements lie in the interior chiefly in the Ord and Fitzroy basins.

It was inevitable that white settlements, whether violently or pacifically introduced, should effect fundamental changes in the native economy. On the Queensland coast the white settlers, imbued with the traditional southern fear and distrust of the native and concerned to assure exclusive occupancy of the land for agricultural pursuits, endeavoured to drive the tribes away from the area of settlement decimating them by organised battles and police “punitive” expeditions. To the west penetration was happily more pacific but even here powerful but then unrecognised influences contributed to the same final outcome. It is expedient to examine these in some detail.

- Labour Demand

The white intruder brought with him an inadequate supply of labour for his projected activities and immediately set about making good the deficiency by recruiting to his service young, able-bodied natives of both sexes. As an inducement he offered principally food which the natives found palatable and, in some respects, more easily obtained, more certainly assured, more convenient to prepare and more liberal in supply, that that to which they had been accustomed. As a further inducement, the employer regularly supplied tobacco and sometimes alcohol and opium which offered the native indulgences hitherto beyond his experience.

- Pastoral Development

The new holdings, being unfenced and sparsely watered, it was essential that stock should not be scattered. Natives, even those unemployed, were therefore encouraged by the same devices to stay more or less permanently in the vicinity of the homestead or its outstations and to abandon the migration and hunting pursuits calculated to harass and impair the condition of stock or disperse them from pastures and waters readily accessible to the stockman.

- Agricultural Development

Cultivation of new crops in virgin soil demanded the destruction or dispersion of native game and the eradication of much of the native food flora.

- Mining

Alluvial working involved widespread destruction of native vegetation along the rich flats adjacent to water courses and the extensive inversion of soil types by the burial of the rich cultivable loam below the unproductive clays, shales and rock excavated from the underlying strata.

- Missions

Mission activity involved the concentration and retention of as many natives as possible in restricted and often ill-chosen areas for indoctrination, moral supervision and education.

The effect of these influences was to render the normal native life more arduous and less attractive. Game was dispersed and many of the sources of vegetable food destroyed or denied. The best hunters and foragers were diverted to new types of labour, their dependents meantime becoming more and more reliant upon white bounty. Simultaneously, the younger native, employed in pursuits about the white settlement or mission was denied the opportunity to develop his hunting arts and skills whilst all were taught new wants which the old life could not satisfy. More and more dependent upon white employment or charity, the natives became concentrated upon limited areas where their natural foods were rapidly depleted by over-population and, where the traditional mode of life having been abandoned, they commenced a type of existence entirely alien to their experience and once which involved dangers which none – whether white or black – was concerned to observer or avert.

Concentration in camps on missions or in the vicinity of white settlements, led to the creation of deplorable conditions of insanitation. The native, knowing nothing of the fundamentals of hygiene and enjoying no guidance from enlightened whites, brought to the new community life these negligent habits of excreta and waste disposal evolved under his historic security as a nomad. Ill-ventilated and unlighted huts built from waste material replaced the temporary brush whurlies. Camps were disposed without regard to water pollution – indeed to take advantage of the sandy ground and to secure shelter from the cold southerly winds they were often sited in river beds. The vicinity quickly became fouled with excreta and wastes, continuing so until the huts were burned and their occupants moved to another site by exasperated whites. This insanitation was a feature alike of mission and station camps. Fifty years after the foundation of some missions it could still be reported by official observers that no organised method of night soil disposal had been devised for native use and only primitive arrangements existed for the Europeans. Charged with neglect of elementary hygiene, the stereotyped reply of missionaries given emphatically and often derisively was the positive assertion that it is impossible to teach the native sanitation because it is contrary to his racial custom.

This is an ingenuous admission of misdirected effort in one persisting with apparent confidence and optimism in the eradication of native culture and the substitution of an unfamiliar religion and an alien economy. In truth, it must be accepted for what it is, an impudent and ill-considered subterfuge to conceal culpable negligence.

In the final result, disease has effected, in the areas of pacific penetration, as tragic a decline in native population as did condoned slaughter in the region of hostile incursion.

In the Queensland section the native population is estimated at 8,000 of which 44% are in Government settlements or missions and the remainder on country reserves, in camps near country towns or in employment on cattle stations.

The native population of the Northern Territory section above the 19th parallel is estimated at 5,000. These include about 2,000 living as nomads on reserves or in contact with missions. The remainder are concentrated on missions, in Government settlements, in camps around townships or in employment on cattle stations. Practically all of these may be regarded as at some time reverting to bush life in their own tribal country for variable periods.

In the Kimberleys, the native population is estimated as 6,000. Approximately half of these live as nomads with more or less transient mission or station contact. The remainder live more or less permanently in association with white settlement, town, mission or rural.

The tropical diseases confronted in Northern Australia include malaria, hookworm, leprosy, leptospirosis, certain fevers of the typhus group, dengue and filariasis. The four last-named are not limited to the region here discussed and with the exception of dengue, are endemic only in a very small fraction of its total area. They have not at any time constituted a special problem of native health and will not be further considered here.

Malaria

The early history of malaria here is obscure. The British Garrison on Melville Island (1825-29) suffered a great deal from “fever”. How much of this as enteric, how much dengue and how much, if any, malaria, is unknown. Benign tertian malaria appeared at Port Essington in the fifth year of occupation following introduction by Macassars. It affected natives near the station but did not extend inland or down the coast. There is no record of subtertian malaria at the Port Essington settlement (1837 – 49) nor did Leichhardt (Port Essington, 1844), Kennedy (peninsula and Carpentaria, 1845-48), Gregory and Von Mueller (Victoria and Roper Rivers, 1856), Burke (Carpentaria, 1861), Walker (Carpentaria, 1861), Stuart (Port Darwin, 1862), Jardine (Peninsula, 1864) or Forrest (Kimberley, 1879) encounter it in their explorations through this region. Von Mueller (1856) positively stated that malaria did not exist at this period in Northern Australia. There is no record of malaria interfering with the construction of the overland telegraph line (1870-72) notwithstanding the use of a base on the Limmen River and a line of porterage across what years afterwards became the nursery of falciparum malaria in the Northern Territory.

The first undoubted record of malaria relates to the ill-fated settlement at Burketown (1864) when, following the arrival there of a proa, with a similar illness amongst its Javanese crew, 50 of the 76 settlers died of a bilious remittent fever. The fact that it was regarded by the settlers as yellow fever suggests that the syndrome was new to their experience. This condition persisted in the Burketown area and for several years a heavy mortality was recorded. Whether the Javanese brought the infection – clearly falciparum – with them or themselves contracted it along the Gulf coast cannot now be known but it is significant that Jardine in the same year traversed the Peninsula from south to north without mooting malaria.

In 1867 J.A. White described malaria as one of the Gulf fevers. A later record is that of Parry Okeden who found the Superintendent of Mapoon Mission near the northern tip of Cape York Peninsula dangerously ill with “fever” in 1896.

In the Cairns area according to Ford, the story of malaria has been one of the rise and fall in incidence of benign tertian, believed to have been introduced by the Melanesian immigration of 1870 and subsequently. Malaria was still very common in 1900. By 1908 it seems to have disappeared except from households on the outskirts of the city, many of them occupied by native and native hybrids. In 1918 Breinl found a parasite rate of 13.5 (both vivax and falciparum) in this area. Following an epidemic in 1922 Rockefeller Foundation investigators in 1923 found a 3% carrier rate in the same neighbourhood and a 7% rate amongst natives at Yarrabah Mission on the adjacent coast. Malaria had disappeared from Cairns by 1927 (Heydon) and did not recur until re-introduced by troops from New Guinea in 1942.

In the Peninsula and Carpentaria Divisions information is far from complete. Falciparum malaria is said to have been epidemic on the Peninsula gold fields in 1901 and to have continued in sporadic outbreaks annually thereafter. In 1910 falciparum malaria at Kidston caused 24 deaths in a population of 400. In 1921-22 Charlton of the Rockefeller Foundation reported that falciparum malaria was endemic throughout the Gulf country and along the western coast of Cape York Peninsula. In none of these outbreaks was the morbidity or mortality amongst natives recorded.

In the Northern Territory epidemics of falciparum malaria have occurred on several occasions:-

- 1879-81 in the Pine Creek railway construction camps;

- 1908-10 on the Umbrawarra tin fields;

- 1913 amongst natives on Melville Island;1916-21 in the Katherine Railway construction camps extending to pastoral districts across the Territory from east to west during 1918-21;

- 1929 on the headwaters of the Limmen River involving railway construction camps at Katherine and Mataranka 1930-31 and the inland pastoral districts 1932-33.

Apparently the 1911 epidemic on Melville Island in which at least 30 natives died, was localised and did not recur, surveys in 1913, 1922, 1928, 1937 and 1943 revealing no malaria.

A Territory wide survey in 1922 detected no parasite rate amongst natives, although two European cases of falciparum malaria were admitted to Darwin Hospital from Brook’s Creek and Katherine during the currency of the survey. Surveys of the Roper River, Alligator River, Milingimbi, Yirrkala and Groote Island in 1939 and 1943 detected no malaria.

Vivax malaria occurred in-

- 1908-10 with subtertian in the Umbrawarra outbreak, caused an epidemic amongst natives in Darwin goal in 1911 and according to Breinl was in 1912 widely dispersed through the Territory.

- 1933 at Talc Head, Port Darwin, involving a few sporadic cases.

- 1942 in the same locality as a more extensive outbreak and involving Darwin itself. The original of infection was on this occasion traced to a recently arrived Indonesian seaman.

- 1945 on the Roper River.

In Western Australia early records show that following the Halls Creek goldrush, deaths from “intermittent fever and ague” in the Kimberleys were registered almost every year from the epidemic year 1891 to 1935 with peaks in 1904, 1910, 1919-22 and 1934. It will be observed that the epidemic periods more or less synchronise with those of the Northern Territory and North Queensland.

During the 1934 outbreak in Western Australia, 150 natives died before a diagnosis was made. These, and the 30 deaths reported on Melville Island in 1911, are the only figures traced recording the fatality of malaria amongst natives.

These facts appear to warrant the conclusion that neither falciparum nor vivax malaria was endemic amongst natives prior to white settlement, even if they had from time to time been introduced to the coast by visiting Macassars. Their failure to become established may have been due in fact to the difficulties imposed by the then native mode of life and in part by the lack of an adequately sustained prevalence of a suitable vector.

When subsequently introduced by white settlement extending inland-

- vivax malaria has occurred only in small, short-lived epidemics and has never established itself securely either in the coastal region or in the interior.

- falciparum malaria on the coast caused short-lived epidemics and completely disappeared.

In the interior it persisted in epidemic or sporadic form from 1908-1935.

In the coastal region the dominant Anopheles is the sylvan A. bancrofti which has a heavy prevalence of very short duration towards the close of the wet season. The great majority of these mosquitoes is destroyed shortly after emergence by the grass fires to which the region is exposed and by the strong, cool southerly wind of the southeast monsoon. The failure of malaria in either form to become permanently established in the coast regions, particularly where the native life is still nomadic, may perhaps be explained by the transient prevalence of this mosquito and its indifferent qualities as a vector. A. annulipes, on the other hand, is a prolific breeder in the margins of the sunlit, drying pools of the interior and in many inland areas continuous in reasonably density throughout the dry season. It may be sufficiently inhospitable to P. vivax to occasion epidemics but sufficiently hospitable to P. falciparum to maintain infection in a detribalised native population at a level too low for ready detection.

Major epidemics of subtertian have unusually been associated with new concentrations of population and there is a temptation to assume that during the inter-epidemic intervals the disease disappeared, the epidemics originating from re-introduction of the parasite by infected persons from overseas. It is doubtful whether this hypothesis is tenable.

The more enduring persistence, the more frequent relapse rate and the greater prevalence of benign tertian in endemic areas, make it improbable that subtertian malaria would have been re-introduced to the interior in pure strain so often over so many years without the simultaneous introduction of the vivax parasite.

In truth, throughout the inter-epidemic periods sporadic cases of subtertian malaria were reported from various parts of the Territory practically every year. This was true even of years when surveys revealed no carrier rate amongst the native population. Baldwin and Cooling in 1922 discovered no infected natives but two cases of subtertian malaria were admitted to the Darwin Hospital during the currency of their survey.

If it be acknowledged that subtertian persisted from 1908 or earlier, a new difficulty is confronted. How was it maintained in inter-epidemic periods without revealing its endemicity in the native population?

Judged by its prevalence in epidemic times the supposed vector A. annulipes is always prevalent in the endemic area in sufficient numbers to occasion an epidemic. Nor was new concentration of population uniformly a factor precipitating an epidemic in localities where all other factors appeared favourable for widespread transmission. Malaria did not appear in the earlier years of the railway construction camps in 1874, 1925 and 1929. On the contrary, all major inland falciparum epidemics except the first (1908) originated in areas of sparse and static population and involved the great labour camps only secondarily.

Settlers on remote cattle stations in the endemic area lived too, for season after season under conditions apparently identical with those of epidemic times yet local epidemics were intermittent and sporadic cases were haphazard in point of time and place.

To explain these anomalies it might be hypothecated:-

- That A. annulipes is a highly inefficient vector and plays little part in epidemics.

- That some other vector – probably A. punculatus farauti (since identified in this region) normally of very low prevalence, from time to time breeds prolifically to a prevalence sufficient to initiate epidemics.

- In inter-epidemic periods infection is maintained at a very low level of incidence amongst the native either by the few A. punculatus farauti normally present or by the very numerous but inefficient A. annulipes.

A very low parasite rate could easily have escaped the notice of transient and occasional survey parties who had not access to more than a small proportion of the natives even on stations. If subtertian malaria persisted amongst natives in non-epidemic times actual cases must occasionally have occurred. These might well be overlooked by the unenlightened or indifferent employer, particularly as the season of maximum malarial prevalence coincidences with the onset of the cold southerly monsoons when fevers of respiratory origin are very prevalent amongst natives.

If these surmises be accepted, it may be considered that the determining factor in the endemicity and epidemicity of malaria amongst natives is the abandonment of their frequent movement from water to water and their more or less permanent concentration in comparatively large numbers near breeding places of a vector capable of maintaining a low rate of infection in a population of sufficient magnitude exposed for a sufficient length of time.

Hookworm

Hookworm was recognised as a feature of tropical Queensland epidemiology for many years before any energetic action was taken to assess its incident or to prevent its diffusion. It was not until the Rockefeller Foundation undertook an investigational, curative and preventive campaign on a large scale in 1919 that its real incidence and extent were realised.

In 1919 Sawyer reported that on the east coast hookworm had an incident of 18% in the population, exclusion of aboriginals, and 81% in natives. He remarked in 1920 – “It is only occasionally that a community is found where more than 30% of white people are infected – aborigines under similar conditions are apt to be all infected”.

The factors particularly contributing to the high incidence in natives were their practice of promiscuous defaecation and their unshod habit.

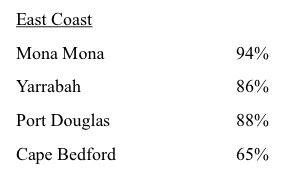

The Hookworm campaign in Queensland during the period 1919-21 revealed the following rates amongst natives on mission stations:-

The incidence in natives living at large outside missions was 19% – a rate comparable to that of the general population.

At all missions, investigating officers reported that gross conditions of insanitation existed in respect of the disposal of night soil. No latrine provision was made for natives and promiscuous defaecation was the rule.

After 30 years the rate at Mona Mona and Daintree (Port Douglas) is still 70%. During the same interval incidence at the Government station at Palm Island has been reduced from 77.2% to 9% by improvement of sanitation and by mass treatment.

Northern Territory – A survey of the Northern Territory was made by Baldwin and Cooling in 1922. Rates reported included:

In 1939 Kirkland reported that the incidence on Bathurst Island was almost 100% and that hookworm endemicity had extended to Katherine and other isolated areas on rivers which had been found free at the time of Baldwin’s survey.

Promiscuous defaecation was here also the rule rather than the exception on missions and elsewhere. Even in the town of Darwin no latrine accommodation was available for natives in employment. Employers would not incur the expense for providing separate latrine accommodation for their employees and would not permit them to use the conveniences provided for the family. Natives were therefore under the necessity of fouling the damp ground in the bush adjacent to their places of employment.

Western Australia – A survey of the north of Western Australia was made by Baldwin in 1922 when the following rates were reported amongst natives:-

As in Queensland and the Northern Territory, promiscuous defaecation was the rule. No organised sanitary system was provided on missions and no special accommodation for native employees available in towns. It is improbable that hookworm was endemic amongst natives prior to white settlement:-

- If it has been brought on to the Australian continent by the natives themselves in their early migration through Asia, it might be expected that there would have been found throughout all endemic areas a roughly uniform species parasitism. Species surveys, conducted by the Rockefeller Foundation however, revealed that in Queensland the predominant species was Nector americanus as is the case in Melanesia. This in itself suggests introduction from Melanesia by the mass immigration of island labour to the canefields of the Queensland cost towards the end of last century. In the Northern Territory, Western Australia and the Gulf, the predominant species was Ankylostoma duodenale suggesting introduction from Asia or southern Europe. Large numbers of Asiatics were imported to Western Australia and the Northern Territory at different times to engage in the pearling industry and to provide a labour force for public works. It is probable that these served as the source of pearling crews conducted in Darwin in 1929 revealed a hookworm rate of 70%. These people were given to promiscuous defaecation in the vicinity of their camps along the northern coast and a few of them were employed on missions as skippers for boats and in other avocations.

- Many areas inhabited by natives, which have subsequently proved favourable for the endemicity of hookworm, were at the time of the surveys found free from infestation. Notable amongst these are Roper River and Elcho Island in the Northern Territory and Derby and Sunday Island in Western Australia. The incident on La Grange Bay in Western Australia was low, having been, according to Baldwin, recently introduced from Broome. At Mornington Island on the Gulf of Carpentaria, incidence on the mission was 84%. On the mainland opposite, hookworm was not found and according to Charlton who conducted the survey, the only natives free from infection at the Mission were those who had recently arrived from the mainland. The incidence on Mitchell River Mission (Charlton) was 20% and amongst Peninsula natives nearby, 5%. Many of the parasitised in the latter group had from time to time visited the Mitchell River Mission.

It seems indisputable that the natives were originally free from hookworm infestation. The disease was introduced to potentially endemic areas by the immigration of parasitised persons following white settlement. The greatest single factor in the subsequent invasion of the native has been his concentration on Mission or Government native stations under conditions of gross insanitation. These establishments have since served as a powerful factor in the infection of new individuals and the repeated reinfection of their charges. The degree of reinfection is emphasised by the fact that at Beagle Bay and Bathurst Island it was not uncommon to find natives with a haemoglobin index as low as 40%.

Leprosy – Queensland: The Queensland Leprosy Act was promulgated in 1892 and prior to that date notification of lepers was haphazard, cases were not specifically sought and epidemiological detail was not systematically recorded.

For the most part information is limited to those concerning whom some fortuitous circumstance occasioned special social interest or administrative embarrassment at the time – hostile demonstrations by alarmed townspeople against the migrant leper, difficulties attending segregation following recognition of leprosy in a prisoner or costs of repatriation.

All cases reported in Queensland during his period were coloured aliens: Chinese immigrants to the goldfields or Melanesian agricultural workers imported to the canefields during the seventies and eighties of the nineteenth century.

Leprosy was not recorded amongst natives until the fifth year of operation of the Leprosy Act – Croydon (1896), Port Douglas (1897). Some twenty native lepers were isolated from the Peninsula and Carpentaria goldfields during the next twelve years.

Information regarding native cases is lamentably incomplete but its apparently exclusive prevalence amongst coloured aliens before 1896 and the five years interval between enforcement of the Leprosy Act and its first recognition in native suggest that Leprosy did not originally exist in the tribes. It seems reasonable to assume that infection was of foreign origin, brought to the mining fields by Chinese and to the canefields by Melanesians, spreading subsequently to the tribal remnants there remaining.

Concentration of these remnants upon Government stations and Missions later led to multiple infections amongst the natives there detained – groups of cases of station origin have been reported from Palm Island, Yarrabah and Mona Mona.

Northern Territory: Records of early British settlement at Fort Dundas, Raffles Bay and Port Essington detailing prevalent diseases amongst natives and the visiting Macassars make no mention of leprosy. In natives the disease was first reported during the last decade of the nineteenth century amongst the Kakadu tribe of the Alligator River in contact with the Chinese Railway Construction labourers and miners in the Burrundie-Pine Creek area. Many cases had been discovered amongst the latter during the previous twenty years.

As late as 1912 Breinl found that leprosy was still confined to the Alligator River tribes, dissemination having presumably been effectually prevented by lack of close association between these natives and their neighbours.

In 1917 it was reported that under the influence of Missions at Goulburn Island and Oenpelli, intertribal barriers were breaking down and in 1925 cases were discovered at both these missions. A forecast then made that the area of endemicity would progressively extend thenceforward has unhappily been fully vindicated.

In 1921 a case was reported from Roper River Mission, dissemination having, it appears, been effected by native migration via the headwaters of the Roper to the endemic area round the railhead. By 1925 fourteen cases occurred amongst natives on this Mission.

At this time natives on the western shore of the Gulf of Carpentaria were still free from infection. This corner of Arnhem land has been the last to come under white influence and traditional tribal life has continued largely undisturbed.

On Groote Island, however, a branch of the Roper River Mission was established and contact between the two settlements was regular. In 1924 two Roper River natives on Groote Island were found to be lepers and in subsequent years the latter mission furnished so many cases that the institution for halfcastes established there was closed by Government direction.

Western Australia: No leprosy was reported amongst natives of the Kimberleys before 1908. In that year there died in Derby a Chinese who had been a leper for many years. Four native cases were discovered shortly afterwards but all died within the year. No later case was reported locally until 1922.

In 1921, however a native leper from Derby was identified at Beagle Bay Mission to the north of Broome. The Mission had at this time been established nearly thirty years and throughout that time had been free from leprosy. By 1932 fifteen native lepers had been removed from the Mission and a further thirty-nine developed symptoms during the next eight years.

A survey of the Kimberleys in 1924 revealed no leprosy beyond the Fitzroy River basin. In 1933, however, a case was discovered on Munja Government Native Station. During the next four years twenty-one new cases were found on Munja. At that time only four cases had occurred on Kunmunya Mission in the same locality but in the years since incidence here too has been heavy. Between 1924 and 1935 only three native lepers had been found in the Halls Creek – Wyndham area. Between 1938 and 1940 twenty-five were discovered here, most of them tracing infection to contact on Munja or Kunmunya.

As late as 1940 the Forrest River, Drysdale River, Gibb River, Kurunjie and Wyndham areas were still practically free. Precise information for the war years and subsequently is lacking but a special survey of this region in 1949 yielded twenty-seven cases and disclosed that leprosy is inexorably extending eastwards. The conclusion is inescapable that the concentration of natives upon missions and Government stations on these rivers will repeat the tragic story of Beagle Bay and Munja, in the years immediately ahead. Native stations play a threefold part in the dissemination of leprosy. They break down intertribal quarantine, they concentrate healthy natives in contact with the infected and disperse them to uninfected areas.

The rapidity and extent of the dissemination of leprosy in the Kimberleys can be more readily appreciated when it is realised that in 1924 the total native leper population ascertained by survey was sixteen. Twenty-five years later it is two hundred and fifty, a figure which take no cognizance of deaths in the intervening years.

To conclude: Malaria, Hookworm and Leprosy did not exist in endemic form amongst the native of Northern Australia prior to white settlement. Malaria, occasionally introduced by visiting Macassar crews, attained no more than a temporary local incidence and disappeared. Hookworm and Leprosy if similarly imported do not seem to have become even locally established and certainly did not diffuse through the tribes. This failure to achieve an endemicity which subsequently proved possible is doubtless to be attributed to the protection afforded by the native mode of life.

With the disruption of native economy following white intrusion these diseases which followed closely in the train of the first settlers found conditions agreeable and once established attained a heavy incidence. Not the least tragic aspect of the story is the paradox that amongst the white population the best intentioned played the major part in precipitating this disaster. Those who made the new life most attractive to the natives, those who painfully and devotedly collected the bedraggled remnant of butchered tribes to afford the sanctuary remote from hostile settlers, those above all who concentrated members of intact tribes in special settlements, the better to instruct them, minister to their physical and spiritual needs and prepare them for the impact of white civilisation, those have created the conditions which have given disease full play.

To-day the incidence of disease in the full blood and hybrid remnant renders the native an object of suspicion and aversion to many in the more densely settled areas. His children must not attend the public schools, he must live in unhygienic improvised shelters beyond the area served by the organised sanitary system, water, light and power services. So, inexorably caught in the vicious cycle of ignorance, degradation and disease, he has become a reservoir of infection endangering the tropical white community – a menace which promises at last to avenge his early and present wrongs more effectually, more impartially and more enduringly than even in his heyday, he could have dreamed possible with his own resources.

And so the ultimate paradox – this ripening harvest of retribution was sown, has been and is being sedulously cultivated unwittingly and with good intent by its future victims.